Articles

The Sinic Analysis

08-30-2023

08-30-2023China in the center of the debt crisis

China will remain a lender in the years ahead, but governments should be more assertive when engaging with China. Demand transparency and openness in your dealings, ensure that local suppliers and local labor is not cut out of the tendering and construction process, and ask tough questions about viability of the project. The days of the China miracle economy are over, and the Belt & Road Initiative is no magic wand which can solve a country’s infrastructure problems.

By Fraser Howie

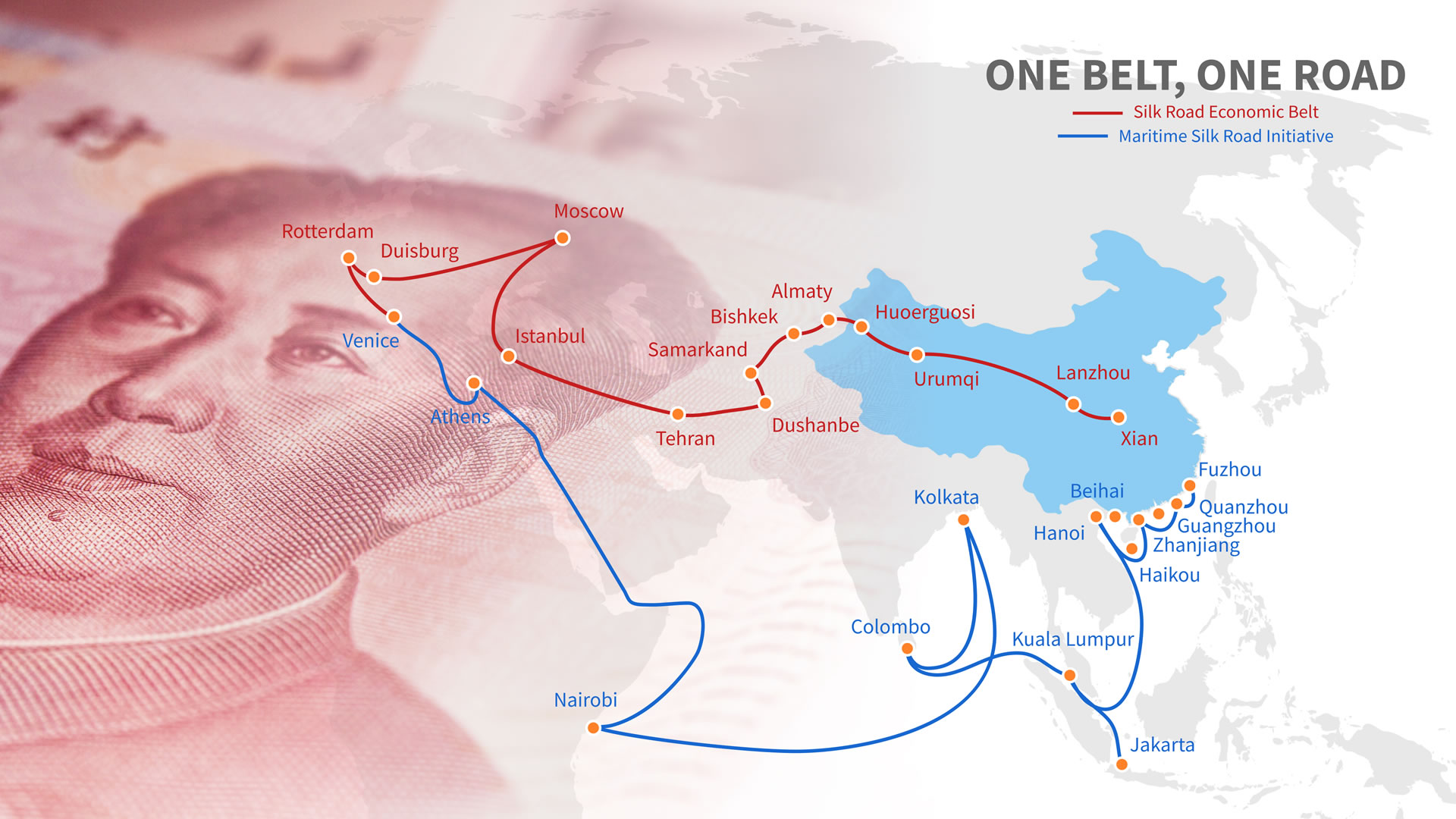

China’s Belt & Road Initiative is about to celebrate its first decade. Wikipedia cites Sept 2013 as the start of Xi Jinping’s landmark project, yet China’s lending and investing across the world long predates that date and the BRI name wasn’t even used in 2013. Originally going by the name One Belt One Road, the project has never been well defined with almost any international project claiming shelter under the BRI banner. Perhaps the better description of the collection of investments and infrastructure development is simply globalization with Chinese characteristics.

What has become clear over the past year is that the BRI is not as simple a win-win type of agreement between China and its BRI participants as the Chinese side like to claim. Indeed, China’s much loved “win-win” formulation has often been seen as China wins twice. The drivers of the BRI project were to export China’s excess production capacity as well as binding countries politically to China in the belief that economics and trade would overcome all political frictions. Much of the lending and investment came through Chinese state-owned enterprises which used Chinese supplies and even Chinese labour to build the infrastructure in the recipient country.

The evidence of the near trillion dollars of lending can be seen across the world in shiny new airports, bridges, and multi-lane highways. This “build it and they will come” model worked to varying degrees as China developed into the factory of the world, but it hasn’t worked to the same degree in other less exciting investment destinations abroad. Many recipient countries are now realizing that a 6-lane highway to the airport isn’t justified given their visitor numbers and that their showcase projects are really “white elephants” with little chance of repaying the debts that funded such hubris.

It would be wrong to characterize the BRI loans as debt traps but there are a number of factors which stood out as red flags when the deals were put together. There was a general lack of transparency of the terms. China always likes to hide terms from public scrutiny and operate bilaterally believing rightly that it gives it more leverage over the recipient country. Such opacity has meant that it has been unclear what the debt load of a given country is, as the Chinese debt is hidden, or the Chinese side insisted on clauses which ensured they were paid out first if it came to a debt restructure. In the Latin American context, Venezuela and Ecuador are good examples of this.

Much of the BRI-related debt was often with a Chinese state-owned corporate not directly with the Chinese state. To those unfamiliar with China a state-owned company sounds a lot like the Chinese state, but the reality is much messier. China’s state-owned enterprises operate like independent fiefdoms and the central state can often struggle to exert influence over the business dealings, or exercise control over the actual companies.

The BRI was never charity, it wasn’t aid, but very much commercial lending often at relatively high terms. But the cost of the loan was often downplayed as the Chinese were so keen to lend money and build projects with seemingly few strings attached. Lending guaranteed China’s penetration in resource-rich markets such as Latin America.

As interest rates and inflation have risen over the past years many BRI countries find themselves financial distressed and in need to debt restructuring or bailouts. Unlike in previous crises, it is China which is the most significant creditor. The size of the Chinese lending means Chinese engagement must be part of the solution, but the opacity of the deals and the patchwork of deals means that China is very much part of the problem as well.

China has never been through such a cycle of debt restructuring before. Developed market banks and countries have worked under established frameworks of the Paris Club and with the IMF or World Bank to address bailouts, but China chafes as working in such a multilateral approach preferring the bilateral approach.

China dislikes dealing with these debts in multilateral fora because it would require them to be totally honest and upfront about the terms of the deals and the size of lending. They never like openness. They also feel they could be pressured having to take a haircut which they don't want.

Because of the risk of not being fully repaid, to date China has had to restructure over 200 BN USD of deals over the past few years. They have chosen to follow the preferred method within China and just extend the terms of the loan effectively just kicking the can further down the road and not really addressing the issue. But domestically that problem is being tested, as it never has before, with a collapse in economic growth brought about by years of malinvestment in infrastructure and a collapse in consumer spending.

The BRI isn’t going away, it is too politically important for Xi Jinping to cast aside but the Chinese state simply doesn’t have the same capacity or willingness to engage in such large overseas activities when it has such a broad range of domestic economic problems. This is something for Latin American governments to think about.

China will remain a lender in the years ahead, but governments should be more assertive when engaging with China. Demand transparency and openness in your dealings, ensure that local suppliers and local labor is not cut out of the tendering and construction process, and ask tough questions about viability of the project. The days of the China miracle economy are over, and the BRI is no magic wand which can solve a country’s infrastructure problems. Recipient countries should be bolder in ensuring they get some of the “win-win”.

Fraser HowieHe studied Physics at Cambridge University and Chinese at Beijing Language and Culture University. He is co-author of three books on China’s financial system, "Red Capitalism: The Fragile Financial Foundations of China’s Extraordinary Rise" (named 2011 Book of the Year by The Economist magazine and one of the top ten business books of the year by Bloomberg), "Privatizing China: Inside China’s Stock Markets" and "To Get Rich is Glorious" China’s Stock Market in the ’80s and ’90s". His writings have appeared in Nikkei Asian Review, Reuters and Japan’s GRICI, and he is a frequent guest on Deutsche Welle, Bloomberg and the BBC. He is a contributor to Análisis Sínico at www.cadal.org.

Fraser HowieHe studied Physics at Cambridge University and Chinese at Beijing Language and Culture University. He is co-author of three books on China’s financial system, "Red Capitalism: The Fragile Financial Foundations of China’s Extraordinary Rise" (named 2011 Book of the Year by The Economist magazine and one of the top ten business books of the year by Bloomberg), "Privatizing China: Inside China’s Stock Markets" and "To Get Rich is Glorious" China’s Stock Market in the ’80s and ’90s". His writings have appeared in Nikkei Asian Review, Reuters and Japan’s GRICI, and he is a frequent guest on Deutsche Welle, Bloomberg and the BBC. He is a contributor to Análisis Sínico at www.cadal.org.

China’s Belt & Road Initiative is about to celebrate its first decade. Wikipedia cites Sept 2013 as the start of Xi Jinping’s landmark project, yet China’s lending and investing across the world long predates that date and the BRI name wasn’t even used in 2013. Originally going by the name One Belt One Road, the project has never been well defined with almost any international project claiming shelter under the BRI banner. Perhaps the better description of the collection of investments and infrastructure development is simply globalization with Chinese characteristics.

What has become clear over the past year is that the BRI is not as simple a win-win type of agreement between China and its BRI participants as the Chinese side like to claim. Indeed, China’s much loved “win-win” formulation has often been seen as China wins twice. The drivers of the BRI project were to export China’s excess production capacity as well as binding countries politically to China in the belief that economics and trade would overcome all political frictions. Much of the lending and investment came through Chinese state-owned enterprises which used Chinese supplies and even Chinese labour to build the infrastructure in the recipient country.

The evidence of the near trillion dollars of lending can be seen across the world in shiny new airports, bridges, and multi-lane highways. This “build it and they will come” model worked to varying degrees as China developed into the factory of the world, but it hasn’t worked to the same degree in other less exciting investment destinations abroad. Many recipient countries are now realizing that a 6-lane highway to the airport isn’t justified given their visitor numbers and that their showcase projects are really “white elephants” with little chance of repaying the debts that funded such hubris.

It would be wrong to characterize the BRI loans as debt traps but there are a number of factors which stood out as red flags when the deals were put together. There was a general lack of transparency of the terms. China always likes to hide terms from public scrutiny and operate bilaterally believing rightly that it gives it more leverage over the recipient country. Such opacity has meant that it has been unclear what the debt load of a given country is, as the Chinese debt is hidden, or the Chinese side insisted on clauses which ensured they were paid out first if it came to a debt restructure. In the Latin American context, Venezuela and Ecuador are good examples of this.

Much of the BRI-related debt was often with a Chinese state-owned corporate not directly with the Chinese state. To those unfamiliar with China a state-owned company sounds a lot like the Chinese state, but the reality is much messier. China’s state-owned enterprises operate like independent fiefdoms and the central state can often struggle to exert influence over the business dealings, or exercise control over the actual companies.

The BRI was never charity, it wasn’t aid, but very much commercial lending often at relatively high terms. But the cost of the loan was often downplayed as the Chinese were so keen to lend money and build projects with seemingly few strings attached. Lending guaranteed China’s penetration in resource-rich markets such as Latin America.

As interest rates and inflation have risen over the past years many BRI countries find themselves financial distressed and in need to debt restructuring or bailouts. Unlike in previous crises, it is China which is the most significant creditor. The size of the Chinese lending means Chinese engagement must be part of the solution, but the opacity of the deals and the patchwork of deals means that China is very much part of the problem as well.

China has never been through such a cycle of debt restructuring before. Developed market banks and countries have worked under established frameworks of the Paris Club and with the IMF or World Bank to address bailouts, but China chafes as working in such a multilateral approach preferring the bilateral approach.

China dislikes dealing with these debts in multilateral fora because it would require them to be totally honest and upfront about the terms of the deals and the size of lending. They never like openness. They also feel they could be pressured having to take a haircut which they don't want.

Because of the risk of not being fully repaid, to date China has had to restructure over 200 BN USD of deals over the past few years. They have chosen to follow the preferred method within China and just extend the terms of the loan effectively just kicking the can further down the road and not really addressing the issue. But domestically that problem is being tested, as it never has before, with a collapse in economic growth brought about by years of malinvestment in infrastructure and a collapse in consumer spending.

The BRI isn’t going away, it is too politically important for Xi Jinping to cast aside but the Chinese state simply doesn’t have the same capacity or willingness to engage in such large overseas activities when it has such a broad range of domestic economic problems. This is something for Latin American governments to think about.

China will remain a lender in the years ahead, but governments should be more assertive when engaging with China. Demand transparency and openness in your dealings, ensure that local suppliers and local labor is not cut out of the tendering and construction process, and ask tough questions about viability of the project. The days of the China miracle economy are over, and the BRI is no magic wand which can solve a country’s infrastructure problems. Recipient countries should be bolder in ensuring they get some of the “win-win”.

Leer esta nota en Español

Leer esta nota en Español