Articles

International Relations and Human Rights Observatory

08-26-2019

08-26-2019Migration crises and regional governance: The cases of Europe, North America and South America

Agreements in which destination countries, which are usually developed democracies, pay for not having to accept more migrants, are not what humanitarian advocates who argue in favor of international cooperation to face migration crises usually have in mind. However, cooperation to restrict immigration is more common worldwide than is cooperation in a liberal direction.

By Sybil Rhodes and Maëliss Bodenan

In June of this year, the United States of America reached an agreement on immigration matters with Mexico. President Donald Trump had threatened to impose tariffs on Mexican exports if the country did not agree to host people fleeing difficult conditions, usually in the Northern Triangle of Central America (Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras), and heading north with the intention of asking for political asylum. The main objective of the deal is to discourage people without a visa from reaching the United States border. Since 2002 there has been an agreement of this type with Canada, and similar arrangements are currently being contemplated with some Central American countries.

The proposals of the United States government would appear to be inspired by the European migration governance model, including the Dublin Convention, which requires that migrants can only apply for asylum in the first country capable of protecting them, and thus avoid forum-shopping. The deal with Mexico is also similar to the immigration agreement closed by the European Union and Turkey in March 2016. In exchange for the promise of 6 billion Euros, Turkey agreed to give shelter to migrants whose intention was to seek refuge in Europe. In both cases, we see the states of "destiny" offering, or imposing, economic incentives in exchange for migration measures in "transit" countries of migration.

Agreements in which destination countries, which are usually developed democracies, pay for not having to accept more migrants, are not what humanitarian advocates who argue in favor of international cooperation to face migration crises usually have in mind. However, as the book Migration crises and the Structure of International Cooperation by Jeannette Money and Sarah Lockhart demonstrates, multilateral cooperation to restrict immigration is more common worldwide than is cooperation in a liberal direction. These authors highlight that receiving countries frequently seek agreements to deport migrants to their country of origin, or directly prevent them from arriving. But since they care about their international reputation as countries that respect human rights, then they try to adhere to the minimum commitments under international law. Arrangements with transit countries, which could be called “pay to keep them out,” and which converts the latter into “buffers,” do not violate the letter of the United Nations Refugee Statute, which obliges adherents to consider the asylum requests of people who reach their borders, but does not specify the right of individuals to choose the particular country where they apply for asylum.

While it can be argued that they are legal, and the idea of distributing responsibility for migration governance among countries of different levels of development is not inherently unreasonable, in practice agreements of the type "money to keep them out" can have serious humanitarian consequences, because they encourage migrants to take more dangerous and illegal routes, causing tragedies like the mass drownings we have seen in the Mediterranean in recent years. Media coverage of these disasters increases perceptions of severe crisis, inspiring some people to take heroic measures to help the desperate, but causing fear and xenophobia in many others.

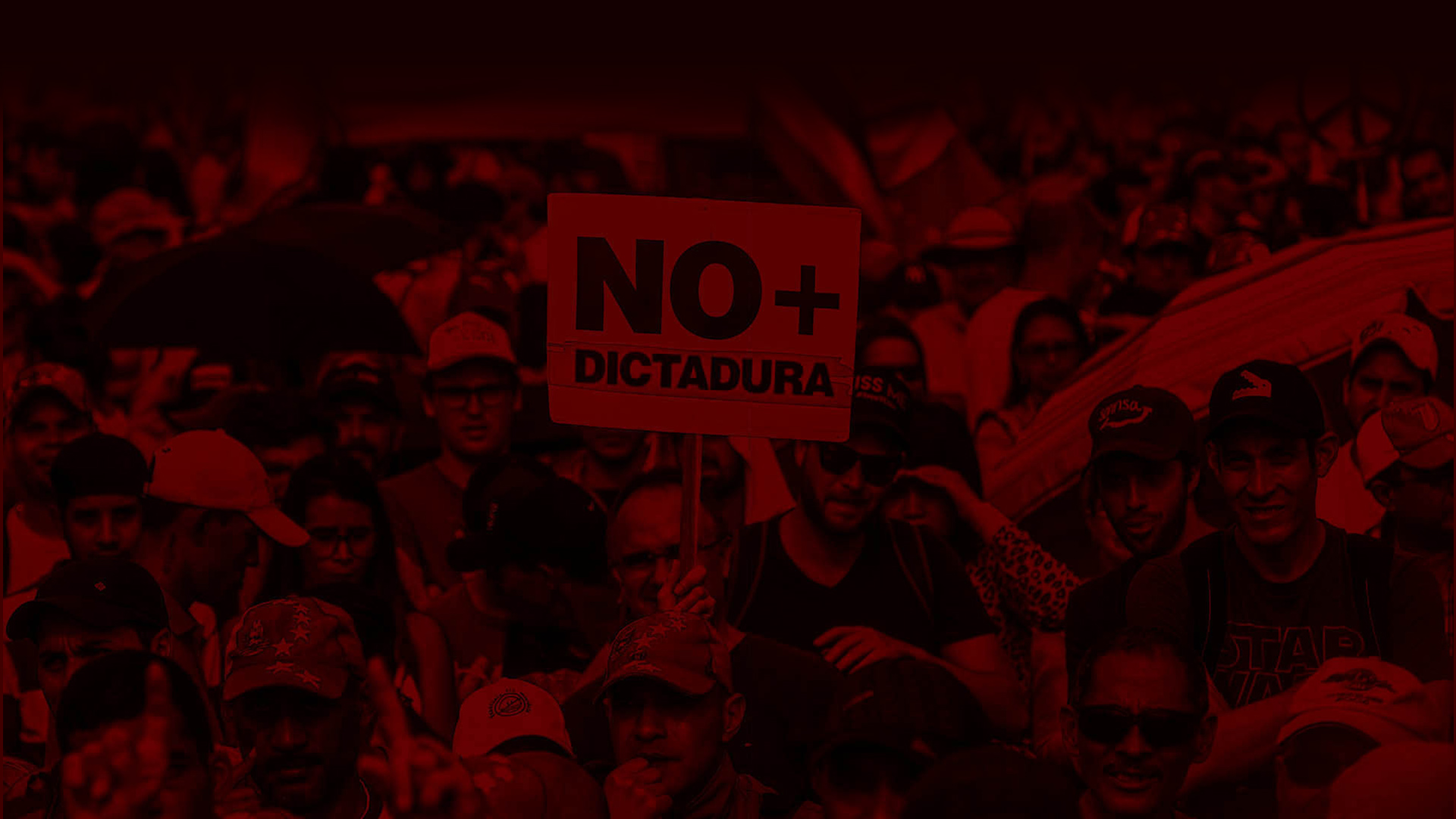

Currently South America is dealing with the effects of outflows of Venezuelans, which began in 2015 and show no signs of stopping. This is a migration of historic proportions, the largest ever in Latin America: it is estimated that there will be 5.4 million Venezuelans abroad at the end of 2019. Colombia has received the largest number, but there are also many Venezuelans in Panama, Peru, Brazil, Ecuador, Chile and Argentina. Is it possible authorities will implement restrictive migration cooperation in this region? More generally, what can we learn by comparing the governance of the South American migration crisis with that of Europe and the United States?

In all three cases, geography determines that not all countries on the continent are equally impacted by migration. In 2018, some 870,000 Venezuelans went to live in Colombia, 9 times more than in Argentina. Colombia could be compared to Turkey, but perhaps the most suitable European comparison would be Italy, a country that has complained about the lack of willingness of its regional peers to share the responsibility of receiving migrants. It is true that a European policy of refugee quotas according to GDP and population (i.e., “burden sharing”) was a failure: many countries, especially Eastern European countries did not implement the Commission's decisions. Colombia has received help from international and philanthropic organizations to welcome migrants, but more is needed. In Latin America, a formal burden sharing system has not been created. However, no strong complaints from Colombian leaders against other South American countries have been heard, and no attempt has been made so far to link the migration crisis with trade measures.

The governments of the region seem to understand that it is better for Venezuelans to enter through the front door, that is, with legal status, from the beginning. Most countries have maintained and / or extended the existing travel regime, which is fairly open. In some cases, a special visa program has been implemented to guarantee legal status. Some governments have given express facilities and procedures for migrating Venezuelans, such as, for example, the recognition of the validity of passports and identity documents after their expiration date. These measures have received praise in international media that contrasts with coverage of the European or North American cases.

However, in the face of an exodus that seems unstoppable, South American governments have also begun to make decisions to limit migratory flows. For example, Peru and Ecuador chose to request a visa from Venezuelans to enter the country, and Colombia implemented a Special Permit for Permanence. Therefore, it seems that a more regional solution needs to be found, probably a less formal and therefore more flexible agreement than the Dublin Convention. It would be an example of the advantages of soft law, and also of the virtues of Latin American regionalism, in some ways more natural than the European version because of the linguistic and cultural ties that countries share. Indeed, regional solidarity is necessary to face a migratory crisis and to facilitate the reception and integration of migrants, and South America is in a position to give refuge to Venezuelans.

It is shameful that the United States has stooped to the point of deliberately separating families as an incentive to curb immigration, and that in Europe relatively small numbers of refugees have caused political crises across the entire continent. However, issues of scale must be taken into account. North America and Europe harbor, in absolute and proportional terms, many more migrants than Latin America. In the case of the United States, a quarter of these migrants are undocumented. Although it is sad to admit this from a cosmopolitan vision, this situation can be difficult to maintain in democratic regimes. The world must find solutions that avoid giving citizens the feeling that their governments have lost control of migration and created a permanent crisis, but at the same time reduce the cruelties that have been seen in recent years.

Sybil Rhodes and Maëliss Bodenan

Sybil Rhodes and Maëliss Bodenan

In June of this year, the United States of America reached an agreement on immigration matters with Mexico. President Donald Trump had threatened to impose tariffs on Mexican exports if the country did not agree to host people fleeing difficult conditions, usually in the Northern Triangle of Central America (Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras), and heading north with the intention of asking for political asylum. The main objective of the deal is to discourage people without a visa from reaching the United States border. Since 2002 there has been an agreement of this type with Canada, and similar arrangements are currently being contemplated with some Central American countries.

The proposals of the United States government would appear to be inspired by the European migration governance model, including the Dublin Convention, which requires that migrants can only apply for asylum in the first country capable of protecting them, and thus avoid forum-shopping. The deal with Mexico is also similar to the immigration agreement closed by the European Union and Turkey in March 2016. In exchange for the promise of 6 billion Euros, Turkey agreed to give shelter to migrants whose intention was to seek refuge in Europe. In both cases, we see the states of "destiny" offering, or imposing, economic incentives in exchange for migration measures in "transit" countries of migration.

Agreements in which destination countries, which are usually developed democracies, pay for not having to accept more migrants, are not what humanitarian advocates who argue in favor of international cooperation to face migration crises usually have in mind. However, as the book Migration crises and the Structure of International Cooperation by Jeannette Money and Sarah Lockhart demonstrates, multilateral cooperation to restrict immigration is more common worldwide than is cooperation in a liberal direction. These authors highlight that receiving countries frequently seek agreements to deport migrants to their country of origin, or directly prevent them from arriving. But since they care about their international reputation as countries that respect human rights, then they try to adhere to the minimum commitments under international law. Arrangements with transit countries, which could be called “pay to keep them out,” and which converts the latter into “buffers,” do not violate the letter of the United Nations Refugee Statute, which obliges adherents to consider the asylum requests of people who reach their borders, but does not specify the right of individuals to choose the particular country where they apply for asylum.

While it can be argued that they are legal, and the idea of distributing responsibility for migration governance among countries of different levels of development is not inherently unreasonable, in practice agreements of the type "money to keep them out" can have serious humanitarian consequences, because they encourage migrants to take more dangerous and illegal routes, causing tragedies like the mass drownings we have seen in the Mediterranean in recent years. Media coverage of these disasters increases perceptions of severe crisis, inspiring some people to take heroic measures to help the desperate, but causing fear and xenophobia in many others.

Currently South America is dealing with the effects of outflows of Venezuelans, which began in 2015 and show no signs of stopping. This is a migration of historic proportions, the largest ever in Latin America: it is estimated that there will be 5.4 million Venezuelans abroad at the end of 2019. Colombia has received the largest number, but there are also many Venezuelans in Panama, Peru, Brazil, Ecuador, Chile and Argentina. Is it possible authorities will implement restrictive migration cooperation in this region? More generally, what can we learn by comparing the governance of the South American migration crisis with that of Europe and the United States?

In all three cases, geography determines that not all countries on the continent are equally impacted by migration. In 2018, some 870,000 Venezuelans went to live in Colombia, 9 times more than in Argentina. Colombia could be compared to Turkey, but perhaps the most suitable European comparison would be Italy, a country that has complained about the lack of willingness of its regional peers to share the responsibility of receiving migrants. It is true that a European policy of refugee quotas according to GDP and population (i.e., “burden sharing”) was a failure: many countries, especially Eastern European countries did not implement the Commission's decisions. Colombia has received help from international and philanthropic organizations to welcome migrants, but more is needed. In Latin America, a formal burden sharing system has not been created. However, no strong complaints from Colombian leaders against other South American countries have been heard, and no attempt has been made so far to link the migration crisis with trade measures.

The governments of the region seem to understand that it is better for Venezuelans to enter through the front door, that is, with legal status, from the beginning. Most countries have maintained and / or extended the existing travel regime, which is fairly open. In some cases, a special visa program has been implemented to guarantee legal status. Some governments have given express facilities and procedures for migrating Venezuelans, such as, for example, the recognition of the validity of passports and identity documents after their expiration date. These measures have received praise in international media that contrasts with coverage of the European or North American cases.

However, in the face of an exodus that seems unstoppable, South American governments have also begun to make decisions to limit migratory flows. For example, Peru and Ecuador chose to request a visa from Venezuelans to enter the country, and Colombia implemented a Special Permit for Permanence. Therefore, it seems that a more regional solution needs to be found, probably a less formal and therefore more flexible agreement than the Dublin Convention. It would be an example of the advantages of soft law, and also of the virtues of Latin American regionalism, in some ways more natural than the European version because of the linguistic and cultural ties that countries share. Indeed, regional solidarity is necessary to face a migratory crisis and to facilitate the reception and integration of migrants, and South America is in a position to give refuge to Venezuelans.

It is shameful that the United States has stooped to the point of deliberately separating families as an incentive to curb immigration, and that in Europe relatively small numbers of refugees have caused political crises across the entire continent. However, issues of scale must be taken into account. North America and Europe harbor, in absolute and proportional terms, many more migrants than Latin America. In the case of the United States, a quarter of these migrants are undocumented. Although it is sad to admit this from a cosmopolitan vision, this situation can be difficult to maintain in democratic regimes. The world must find solutions that avoid giving citizens the feeling that their governments have lost control of migration and created a permanent crisis, but at the same time reduce the cruelties that have been seen in recent years.