Articles

International Relations and Human Rights Observatory

04-25-2022

04-25-2022Business and interests: the allies that support Moscow

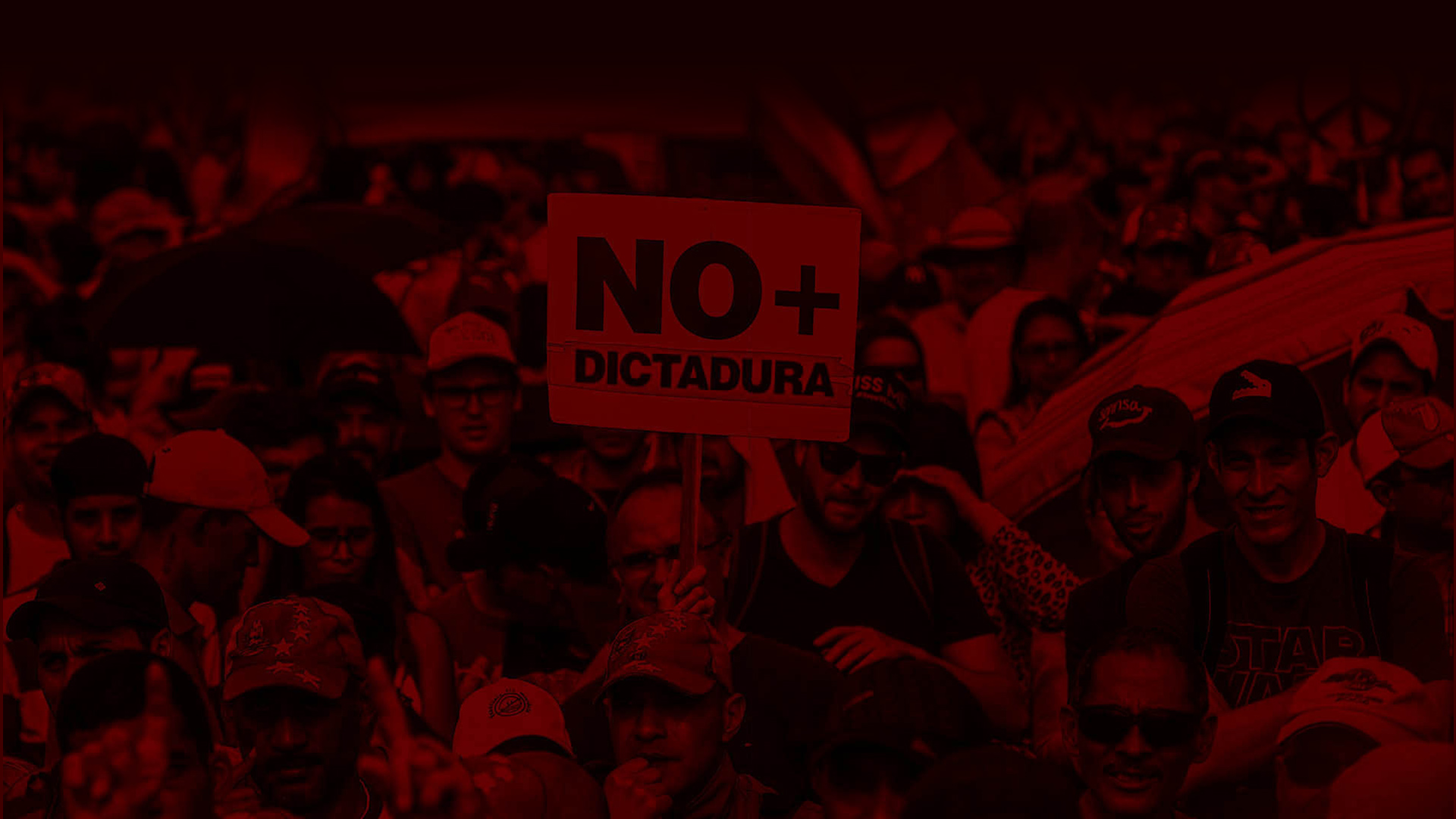

Not all authoritarian or semi-authoritarian regimes are allies of Moscow, but all Moscow’s allies are authoritarian regimes. When the United Nations General Assembly voted in March to condemn the Russian invasion of Ukraine, only five states opposed it: Belarus, North Korea, Eritrea, Syria and Russia itself. In April, the same organization voted to suspend Russia in the Human Rights Council and this time there were 24 countries that supported the Kremlin. Among others, Cuba, China, Iran, Kazakhstan, Nicaragua, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Vietnam joined. And Venezuela should probably also be included, but its right to vote is suspended. All these countries are ruled by dictatorships.

By Ignacio E. Hutin

Putin en la 70ª sesión de la Asamblea General de la Organización de las Naciones Unidas en Nueva York (2015).The Russian invasion to Ukraine has already exceeded two months and there does not seem to be any quick way out, either negotiated or military. The Kremlin cannot back down now, having insisted so much to its own citizens and through the media owned directly or indirectly by the Russian state (that is, through all Russian media) that Ukraine is a Nazi country, a constant threat to Russia's security. But Ukraine cannot give up either. It is difficult to imagine that Kyiv will surrender and submit to Moscow's demands, especially when it comes to ceding territories claimed by its neighbor: the Crimean peninsula, the eastern region of Donbass and even other areas of Ukraine that have been attacked in the south of the country, such as the provinces of Zaporizhia, Kherson, Mikolaiv and Odessa. The war then seems doomed to stagnation, to last indefinitely, despite the fact that certain Western states contribute with weapons and financing to the Ukrainian resistance. And it is that, in addition to its military power and its role as a major supplier of hydrocarbons, Russia has some important support. Even in the European Union itself.

Vladimir Putin's main ally in Europe is Belarus and its leader Aleksandr Lukashenko, president since 1994. Until August 2020, he had tried to get some distance from Moscow and show himself as an autonomous and powerful figure, even flirting with members of the European Union. But few believed the official results of the presidential elections that month: 81% in favor of the leader. The protests were massive, the largest that had been seen in the history of Belarus; and the State responded with repression, with tens of thousands of arrests and torture of thousands of citizens. The efforts and sacrifices from a civil society mobilized like never before were not enough to bring down the almighty president of Minsk. Even so, Lukashenko's regime was weakened, so much so that he had to ask for help from Russia. Since then, Belarus has been practically an annex of the Kremlin, in addition to being the least democratic country on the continent and one of the 20 least democratic on the planet.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya was a housewife with no political experience and her husband, a blogger who wanted to be a presidential candidate in 2020. But the Lukashenko regime was never very friendly with the democratic opposition. The arrest of Sergei Tikhanovsky pushed his wife to become a symbol of change and the most visible face of the pre-election calls. But, like so many others, she had to go into exile.

Belarus plays today a fundamental role in the framework of the Russian invasion, not only because it is a great ally of Moscow, but also because of its geographical location: it has borders with Ukraine less than 100 kilometers from Kyiv. According to Lukashenko, its Armed Forces do not formally participate in what Putin calls a "special operation", but Minsk has lent its territory for missile launches and as a starting point for the invasion of Russian troops in northern Ukraine. Its role and responsibility in this context is undeniable.

In Amsterdam, Tsikhanouskaya says that it is important to separate the Lukashenko regime from the Belarusian people and insists that citizens, including the soldiers themselves, do not support the invasion. The former presidential candidate explains that her compatriots have shared images of Russian troops and weapons with the Ukrainian army so that their neighbors were prepared, and that there were acts of sabotage, for example on trains transporting military vehicles to Ukraine.

“Our soldiers do not want to fight against the Ukrainian people, they do not understand why they should die or kill for the ambitions of two dictators. I think Lukashenko ordered them to fight in Ukraine, but they didn't want to. Lukashenko thought that he would be on the winning side with Putin, that the war would end quickly. But in the face of Ukrainian courage, he had to change his rhetoric: he now says that Belarus is not participating in the invasion. We all know that he is an accomplice, that he shares the responsibility and that he will have to face the consequences of his crimes”, Tsikhanouskaya says.

On the other hand, April brought two good news for the Kremlin: the very predictable reelections of Viktor Orbán and Aleksandar Vučić in Hungary and Serbia respectively. Orbán assumed his fourth term as Prime Minister, a position he has held since 2010, after defeating an opposition coalition that united all kinds of parties: conservatives, liberals, social democrats, left and right wings, all together to defeat the ruling party Fidesz. But that was not enough and the Hungarian leader retained power with more than 50% of the votes, the largest victory in the 32 years of free elections in Hungary.

Hungary is, along with Romania, the least democratic country in the European Union, according to the Democracy Index elaborated annually by the British weekly The Economist. It also has the worst rates in the continental bloc for political rights and civil liberties, according to the NGO Freedom House, and the second worse freedom of the press, according to Reporters Without Borders, behind Bulgaria. In a country where there is less and less space for the opposition, the government of Viktor Orbán was guaranteed victory.

Orbán is not necessarily a pro-Russian leader, but he has spent years trying to portray himself as an autonomous nationalist, even within the European Union. With this idea in mind, he has openly questioned and criticized the continental bloc many times, especially on issues related to the rights of sexual minorities. His rapprochement with Moscow is not surprising then. In fact, he was the first EU leader to meet with Putin in the framework of the mobilization of Russian troops towards Ukraine's borders. It was in February, just three weeks before the start of the invasion.

On the other hand, Hungary rejected European trade sanctions on the Russian energy sector and announced that, if Moscow so requested, it would pay for its gas imports in rubles, something to which Brussels, the EU headquarters, opposes. In addition, authorities from Budapest not only refused to provide weapons to Ukraine, but also to allow the passage of lethal NATO weapons through its territory.

Orbán talks about maintaining neutrality, or at least that is what he proposed to his voters. According to Fidesz's rhetoric, supporting Ukraine would mean getting involved in a war and putting the entire European Union at risk. Hungary imports 85% of the gas and 60% of the oil it uses from Russia, and the possibility of continuing to receive hydrocarbons at low cost seems much more important than helping a neighboring country in the context of an invasion.

Serbia, for its part, is not part of the EU, but it is Russia's main ally in the Balkans, the only country in the region that is not a member of NATO or a candidate to join the North Atlantic alliance. Vučić's Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) has held the presidency since 2012 and the government since 2016. As a Slavic and Orthodox Christian country, Serbia maintains a very close relationship with Moscow, even as a candidate to join the European Union. So much so that in the streets of Belgrade there have been important manifestations in support of the Russian invasion.

Vučić announced that he would not respond to Brussels' request to tighten trade sanctions on Russia. “We have a kind of protection from Russia. What do Western countries want? That we put aside all our national interests because someone else needs something for itself?" said the Balkan president and added a statement that seems to be in tune with the supposed Hungarian neutrality: "We have not imposed sanctions against anyone because we do not believe that sanctions change anything. They can pressure us and force us, but this is our position. People talk about choosing sides. And no. We have our own side: the interests of Serbia.”

Reviewing Serbia's indices for democracy and civil liberties would show results very similar to Hungary's. But perhaps that would mean making the mistake of assuming that the only countries with authoritarian regimes are those close to Putin. And it would mean to forget Poland, Bulgaria or Slovenia, within the EU, or Albania and Turkey, within NATO, or even Ukraine itself. None of these countries is an ally of Moscow and yet all of them have very low rates of respect for individual freedoms. Perhaps a more accurate conclusion would then be that not all authoritarian or semi-authoritarian regimes are allies of Moscow, but all Moscow's allies are authoritarian regimes.

When the United Nations General Assembly voted in March to condemn the Russian invasion of Ukraine, only five states opposed it: Belarus, North Korea, Eritrea, Syria and Russia itself. In April, the same organization voted to suspend Russia in the Human Rights Council and this time there were 24 countries that supported the Kremlin. Among others, Cuba, China, Iran, Kazakhstan, Nicaragua, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Vietnam joined. And Venezuela should probably also be included, but its right to vote is suspended. All these countries are ruled by dictatorships.

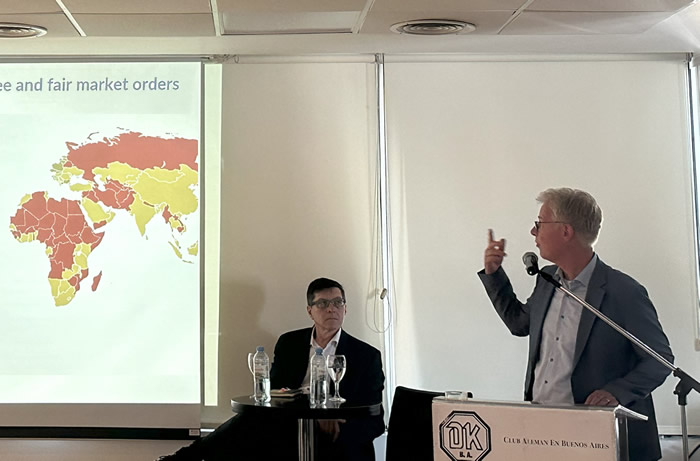

Franak Viačorka, Tsikhanouskaya’s political adviser, commented in Amsterdam that European ties with Moscow are based on fear and interests. But he said that fear is dissipating now that Ukraine, a country much weaker than Russia in military terms, is showing significant resistance. “Ukraine has burst the bubble and Russia no longer seems invincible. Now is a very good opportunity for countries like Belarus, Georgia, Ukraine, Moldova or Armenia”, he said and suggested to stop governing based on interests and instead to build policies on common values: “we must look for the people with whom we share the values of respect for human dignity, human rights, and individual freedoms”.

Perhaps that is a way forward, with European unity as the only way to force a Russian withdrawal. But as long as even Germany, and not just Hungary, Serbia or Belarus, privilege cheap gas over human life, this war seems doomed to continue for far too long.

Ignacio E. HutinAdvisory CouncelorMaster in International Relations (University of Salvador, 2021), Graduate in Journalism (University of Salvador, 2014), specialized in Leadership in Humanitarian Emergencies (National Defense University, 2019) and studied photography (ARGRA, 2009). He is a focused in Eastern Europe, post-Soviet Eurasia and the Balkans. He received a scholarship from the Finnish State to carry out studies related to the Arctic at the University of Lapland (2012). He is the author of the books Saturn (2009), Deconstruction: Chronicles and Reflections from Post-Communist Eastern Europe (2018), Ukraine/Donbass: A Renewed Cold War (2021), and Ukraine: Chronicle from the Frontlines (2021).

Ignacio E. HutinAdvisory CouncelorMaster in International Relations (University of Salvador, 2021), Graduate in Journalism (University of Salvador, 2014), specialized in Leadership in Humanitarian Emergencies (National Defense University, 2019) and studied photography (ARGRA, 2009). He is a focused in Eastern Europe, post-Soviet Eurasia and the Balkans. He received a scholarship from the Finnish State to carry out studies related to the Arctic at the University of Lapland (2012). He is the author of the books Saturn (2009), Deconstruction: Chronicles and Reflections from Post-Communist Eastern Europe (2018), Ukraine/Donbass: A Renewed Cold War (2021), and Ukraine: Chronicle from the Frontlines (2021).

The Russian invasion to Ukraine has already exceeded two months and there does not seem to be any quick way out, either negotiated or military. The Kremlin cannot back down now, having insisted so much to its own citizens and through the media owned directly or indirectly by the Russian state (that is, through all Russian media) that Ukraine is a Nazi country, a constant threat to Russia's security. But Ukraine cannot give up either. It is difficult to imagine that Kyiv will surrender and submit to Moscow's demands, especially when it comes to ceding territories claimed by its neighbor: the Crimean peninsula, the eastern region of Donbass and even other areas of Ukraine that have been attacked in the south of the country, such as the provinces of Zaporizhia, Kherson, Mikolaiv and Odessa. The war then seems doomed to stagnation, to last indefinitely, despite the fact that certain Western states contribute with weapons and financing to the Ukrainian resistance. And it is that, in addition to its military power and its role as a major supplier of hydrocarbons, Russia has some important support. Even in the European Union itself.

Vladimir Putin's main ally in Europe is Belarus and its leader Aleksandr Lukashenko, president since 1994. Until August 2020, he had tried to get some distance from Moscow and show himself as an autonomous and powerful figure, even flirting with members of the European Union. But few believed the official results of the presidential elections that month: 81% in favor of the leader. The protests were massive, the largest that had been seen in the history of Belarus; and the State responded with repression, with tens of thousands of arrests and torture of thousands of citizens. The efforts and sacrifices from a civil society mobilized like never before were not enough to bring down the almighty president of Minsk. Even so, Lukashenko's regime was weakened, so much so that he had to ask for help from Russia. Since then, Belarus has been practically an annex of the Kremlin, in addition to being the least democratic country on the continent and one of the 20 least democratic on the planet.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya was a housewife with no political experience and her husband, a blogger who wanted to be a presidential candidate in 2020. But the Lukashenko regime was never very friendly with the democratic opposition. The arrest of Sergei Tikhanovsky pushed his wife to become a symbol of change and the most visible face of the pre-election calls. But, like so many others, she had to go into exile.

Belarus plays today a fundamental role in the framework of the Russian invasion, not only because it is a great ally of Moscow, but also because of its geographical location: it has borders with Ukraine less than 100 kilometers from Kyiv. According to Lukashenko, its Armed Forces do not formally participate in what Putin calls a "special operation", but Minsk has lent its territory for missile launches and as a starting point for the invasion of Russian troops in northern Ukraine. Its role and responsibility in this context is undeniable.

In Amsterdam, Tsikhanouskaya says that it is important to separate the Lukashenko regime from the Belarusian people and insists that citizens, including the soldiers themselves, do not support the invasion. The former presidential candidate explains that her compatriots have shared images of Russian troops and weapons with the Ukrainian army so that their neighbors were prepared, and that there were acts of sabotage, for example on trains transporting military vehicles to Ukraine.

“Our soldiers do not want to fight against the Ukrainian people, they do not understand why they should die or kill for the ambitions of two dictators. I think Lukashenko ordered them to fight in Ukraine, but they didn't want to. Lukashenko thought that he would be on the winning side with Putin, that the war would end quickly. But in the face of Ukrainian courage, he had to change his rhetoric: he now says that Belarus is not participating in the invasion. We all know that he is an accomplice, that he shares the responsibility and that he will have to face the consequences of his crimes”, Tsikhanouskaya says.

On the other hand, April brought two good news for the Kremlin: the very predictable reelections of Viktor Orbán and Aleksandar Vučić in Hungary and Serbia respectively. Orbán assumed his fourth term as Prime Minister, a position he has held since 2010, after defeating an opposition coalition that united all kinds of parties: conservatives, liberals, social democrats, left and right wings, all together to defeat the ruling party Fidesz. But that was not enough and the Hungarian leader retained power with more than 50% of the votes, the largest victory in the 32 years of free elections in Hungary.

Hungary is, along with Romania, the least democratic country in the European Union, according to the Democracy Index elaborated annually by the British weekly The Economist. It also has the worst rates in the continental bloc for political rights and civil liberties, according to the NGO Freedom House, and the second worse freedom of the press, according to Reporters Without Borders, behind Bulgaria. In a country where there is less and less space for the opposition, the government of Viktor Orbán was guaranteed victory.

Orbán is not necessarily a pro-Russian leader, but he has spent years trying to portray himself as an autonomous nationalist, even within the European Union. With this idea in mind, he has openly questioned and criticized the continental bloc many times, especially on issues related to the rights of sexual minorities. His rapprochement with Moscow is not surprising then. In fact, he was the first EU leader to meet with Putin in the framework of the mobilization of Russian troops towards Ukraine's borders. It was in February, just three weeks before the start of the invasion.

On the other hand, Hungary rejected European trade sanctions on the Russian energy sector and announced that, if Moscow so requested, it would pay for its gas imports in rubles, something to which Brussels, the EU headquarters, opposes. In addition, authorities from Budapest not only refused to provide weapons to Ukraine, but also to allow the passage of lethal NATO weapons through its territory.

Orbán talks about maintaining neutrality, or at least that is what he proposed to his voters. According to Fidesz's rhetoric, supporting Ukraine would mean getting involved in a war and putting the entire European Union at risk. Hungary imports 85% of the gas and 60% of the oil it uses from Russia, and the possibility of continuing to receive hydrocarbons at low cost seems much more important than helping a neighboring country in the context of an invasion.

Serbia, for its part, is not part of the EU, but it is Russia's main ally in the Balkans, the only country in the region that is not a member of NATO or a candidate to join the North Atlantic alliance. Vučić's Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) has held the presidency since 2012 and the government since 2016. As a Slavic and Orthodox Christian country, Serbia maintains a very close relationship with Moscow, even as a candidate to join the European Union. So much so that in the streets of Belgrade there have been important manifestations in support of the Russian invasion.

Vučić announced that he would not respond to Brussels' request to tighten trade sanctions on Russia. “We have a kind of protection from Russia. What do Western countries want? That we put aside all our national interests because someone else needs something for itself?" said the Balkan president and added a statement that seems to be in tune with the supposed Hungarian neutrality: "We have not imposed sanctions against anyone because we do not believe that sanctions change anything. They can pressure us and force us, but this is our position. People talk about choosing sides. And no. We have our own side: the interests of Serbia.”

Reviewing Serbia's indices for democracy and civil liberties would show results very similar to Hungary's. But perhaps that would mean making the mistake of assuming that the only countries with authoritarian regimes are those close to Putin. And it would mean to forget Poland, Bulgaria or Slovenia, within the EU, or Albania and Turkey, within NATO, or even Ukraine itself. None of these countries is an ally of Moscow and yet all of them have very low rates of respect for individual freedoms. Perhaps a more accurate conclusion would then be that not all authoritarian or semi-authoritarian regimes are allies of Moscow, but all Moscow's allies are authoritarian regimes.

When the United Nations General Assembly voted in March to condemn the Russian invasion of Ukraine, only five states opposed it: Belarus, North Korea, Eritrea, Syria and Russia itself. In April, the same organization voted to suspend Russia in the Human Rights Council and this time there were 24 countries that supported the Kremlin. Among others, Cuba, China, Iran, Kazakhstan, Nicaragua, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Vietnam joined. And Venezuela should probably also be included, but its right to vote is suspended. All these countries are ruled by dictatorships.

Franak Viačorka, Tsikhanouskaya’s political adviser, commented in Amsterdam that European ties with Moscow are based on fear and interests. But he said that fear is dissipating now that Ukraine, a country much weaker than Russia in military terms, is showing significant resistance. “Ukraine has burst the bubble and Russia no longer seems invincible. Now is a very good opportunity for countries like Belarus, Georgia, Ukraine, Moldova or Armenia”, he said and suggested to stop governing based on interests and instead to build policies on common values: “we must look for the people with whom we share the values of respect for human dignity, human rights, and individual freedoms”.

Perhaps that is a way forward, with European unity as the only way to force a Russian withdrawal. But as long as even Germany, and not just Hungary, Serbia or Belarus, privilege cheap gas over human life, this war seems doomed to continue for far too long.

Leer esta nota en Español

Leer esta nota en Español