Articles

International Relations and Human Rights Observatory

01-15-2020

01-15-2020Argentina’s controversial foreign policy

(Global Americans) Under Argentina’s new government, foreign policy decisions based more on ideological affinity than on greater pragmatism could bare serious consequences for the country, more so when dealing with non-democratic countries.

By Alejandro Di Franco

(Global Americans) A month after its inauguration, Alberto Fernández’s government in Argentina has received some backlash for its standing on foreign relations issues. Although the administration’s greatest concern is currently set on fixing the country’s economy, foreign relations are proving to be much more challenging than originally thought. The administration seems to be pulled from two different sides, complicating the government’s official standing when responding to world events: on one side is the political affinities of the members of Fernández’s Peronist party, and on the other, is the desire to appear like a moderate government and the need to maintain a good relationship with the United States—seen as essential to address the country’s debt.

Confronted with pressure from both sides, the Argentine Foreign Ministry, headed by Felipe Solá, has sometimes chosen to adopt a more moderate position, as in the case of the U.S.-Iran conflict. However, Solá has also recently made foreign policy decisions that have ignited many controversies, and appear to be guided more by ideology than moderation.

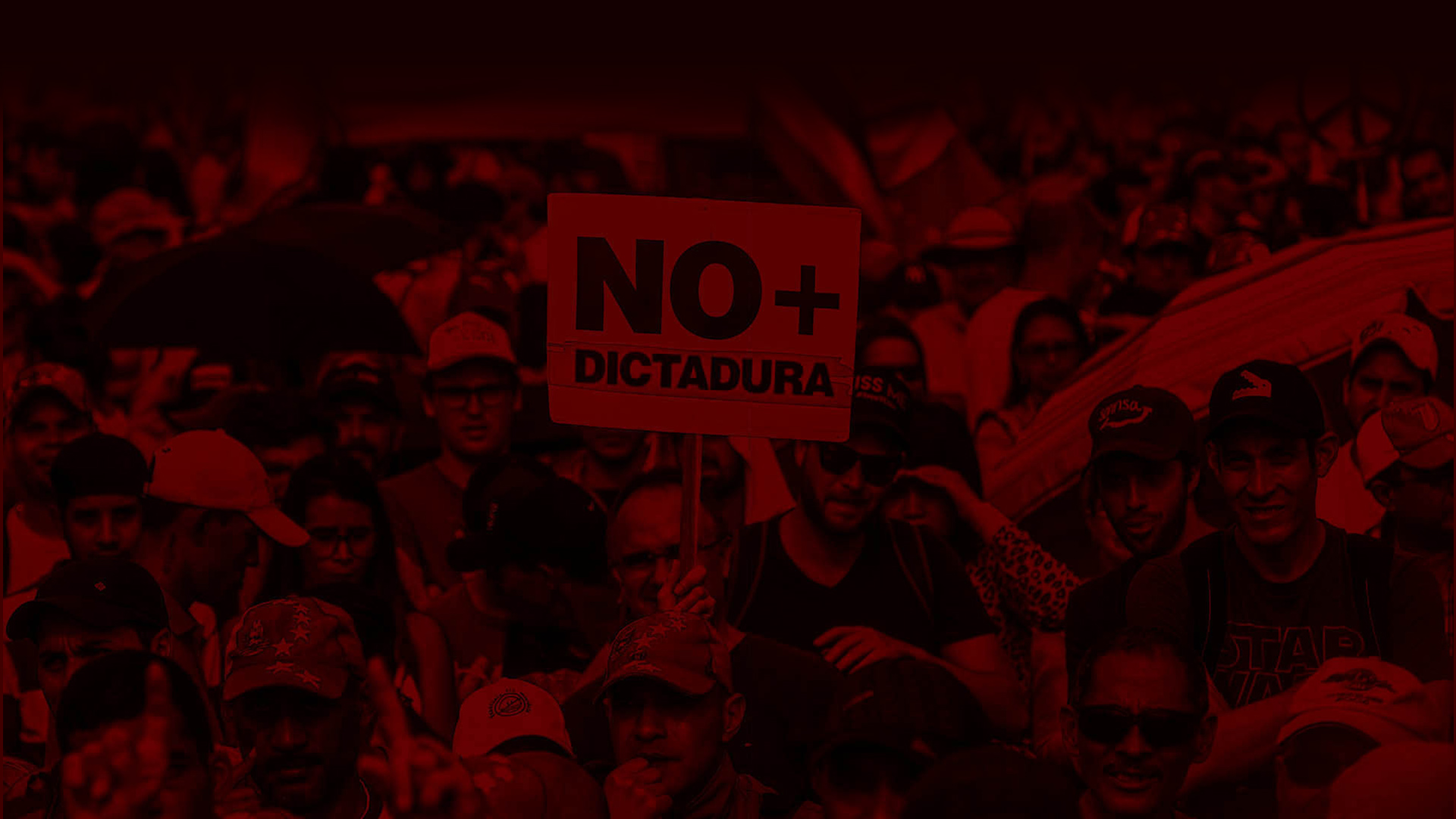

One of the controversial events occurred when Argentina—along with Mexico—refused to sign the Lima Group’s statement condemning “the use of force by the dictatorial regime of Nicolás Maduro to prevent the deputies of the National Assembly from freely accessing the session.” Instead, the Foreign Ministry redundantly condemned the acts that resulted in a “new obstacle to the full functioning of the rule of law.” Yet, this tepid stance was criticized by Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro’s regime, with Speaker of the Constituent Assembly Diosdado Cabello saying that “we do not need Argentina or its foreign minister. They will see on which side they’ll stand, if on the side of the people or the dragged.”

Days later the government made the decision to stop recognizing Elisa Trotta Gamus, Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaidó’s ambassador in Argentina. Prior to the announcement, Gamus had thanked Solá for Argentina’s statement on Venezuela: “We thank Chancellor [Felipe Solá] for his concern over the events that unfolded today in Venezuela. Our fight is to bring back democracy through free presidential elections, to put an end to the unprecedented humanitarian crisis.”

According to Infobae, the Foreign Ministry made the decision because Ambassador Gamus did not have a “diplomatic passport” and because her mission “did not comply with the Vienna Convention.” But Argentina is practically alone in this decision, as many other countries in the region recognize Guaidó’s ambassadors, like Orlando Viera Blanco in Canada, Carlos Vecchio in the U.S., and Guarequena Gutiérrez in Chile.

On another note, while Solá was in Mexico for the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) meeting on January 8, he met with Ecuadorian politician María Fernanda Espinosa, Argentina’s expected pick for the Secretary General position at the Organization of American States (OAS). Espinosa is running against incumbent Secretary General Luis Almagro, who is backed by the United States, Canada, Chile, Uruguay, among others.

Argentina’s support of Espinosa is controversial because she is referred to as “ALBA’s candidate”—referring to the Bolivian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America, founded by Cuba and Venezuela in 2004—for her ideological affinities; she has previously referred to Che Guevara, Fidel Castro and Hugo Chávez as “exemplary” leaders that tried to drive Latin America “to safe harbor.” The former Ecuadorian Minister of Defense and former President of the United Nations General Assembly, who will not be supported by her own country in her bid to replace Almagro, is also criticized for acts of corruption. Espinosa allegedly sought to eliminate parts of the investigation into the murder of Military General Jorge Gabela, who had denounced the irregular purchase of helicopters by the government of Rafael Correa; and allegedly granted identity cards to Iranian citizens with links to terrorist organizations.

These actions have awakened controversy in an area where Argentina has little room to work with. Limited by an internal economic crisis and integrated in a region with scarce strong ideological allies like the ones Argentina could count on back in 2003 when Fernández was Chief of Staff—the Puebla Group does not have a current president beyond Fernández—foreign policy decisions based more on ideological affinity than on greater pragmatism could have significant consequences for Argentina. In terms of principles, although “non-intervention” can be defended as a noble axiom in international relations; many situations, like recognizing one ambassador over another or supporting one candidacy instead of another, require defined positions, which will be all the more controversial when it comes to non-democratic countries, as has started to occur.

Alejandro Di FrancoInternational Relations student at the Universidad Católica Argentina. Former volunteer at the Argentinian Council for International Relations (CARI).

Alejandro Di FrancoInternational Relations student at the Universidad Católica Argentina. Former volunteer at the Argentinian Council for International Relations (CARI).

(Global Americans) A month after its inauguration, Alberto Fernández’s government in Argentina has received some backlash for its standing on foreign relations issues. Although the administration’s greatest concern is currently set on fixing the country’s economy, foreign relations are proving to be much more challenging than originally thought. The administration seems to be pulled from two different sides, complicating the government’s official standing when responding to world events: on one side is the political affinities of the members of Fernández’s Peronist party, and on the other, is the desire to appear like a moderate government and the need to maintain a good relationship with the United States—seen as essential to address the country’s debt.

Confronted with pressure from both sides, the Argentine Foreign Ministry, headed by Felipe Solá, has sometimes chosen to adopt a more moderate position, as in the case of the U.S.-Iran conflict. However, Solá has also recently made foreign policy decisions that have ignited many controversies, and appear to be guided more by ideology than moderation.

One of the controversial events occurred when Argentina—along with Mexico—refused to sign the Lima Group’s statement condemning “the use of force by the dictatorial regime of Nicolás Maduro to prevent the deputies of the National Assembly from freely accessing the session.” Instead, the Foreign Ministry redundantly condemned the acts that resulted in a “new obstacle to the full functioning of the rule of law.” Yet, this tepid stance was criticized by Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro’s regime, with Speaker of the Constituent Assembly Diosdado Cabello saying that “we do not need Argentina or its foreign minister. They will see on which side they’ll stand, if on the side of the people or the dragged.”

Days later the government made the decision to stop recognizing Elisa Trotta Gamus, Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaidó’s ambassador in Argentina. Prior to the announcement, Gamus had thanked Solá for Argentina’s statement on Venezuela: “We thank Chancellor [Felipe Solá] for his concern over the events that unfolded today in Venezuela. Our fight is to bring back democracy through free presidential elections, to put an end to the unprecedented humanitarian crisis.”

According to Infobae, the Foreign Ministry made the decision because Ambassador Gamus did not have a “diplomatic passport” and because her mission “did not comply with the Vienna Convention.” But Argentina is practically alone in this decision, as many other countries in the region recognize Guaidó’s ambassadors, like Orlando Viera Blanco in Canada, Carlos Vecchio in the U.S., and Guarequena Gutiérrez in Chile.

On another note, while Solá was in Mexico for the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) meeting on January 8, he met with Ecuadorian politician María Fernanda Espinosa, Argentina’s expected pick for the Secretary General position at the Organization of American States (OAS). Espinosa is running against incumbent Secretary General Luis Almagro, who is backed by the United States, Canada, Chile, Uruguay, among others.

Argentina’s support of Espinosa is controversial because she is referred to as “ALBA’s candidate”—referring to the Bolivian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America, founded by Cuba and Venezuela in 2004—for her ideological affinities; she has previously referred to Che Guevara, Fidel Castro and Hugo Chávez as “exemplary” leaders that tried to drive Latin America “to safe harbor.” The former Ecuadorian Minister of Defense and former President of the United Nations General Assembly, who will not be supported by her own country in her bid to replace Almagro, is also criticized for acts of corruption. Espinosa allegedly sought to eliminate parts of the investigation into the murder of Military General Jorge Gabela, who had denounced the irregular purchase of helicopters by the government of Rafael Correa; and allegedly granted identity cards to Iranian citizens with links to terrorist organizations.

These actions have awakened controversy in an area where Argentina has little room to work with. Limited by an internal economic crisis and integrated in a region with scarce strong ideological allies like the ones Argentina could count on back in 2003 when Fernández was Chief of Staff—the Puebla Group does not have a current president beyond Fernández—foreign policy decisions based more on ideological affinity than on greater pragmatism could have significant consequences for Argentina. In terms of principles, although “non-intervention” can be defended as a noble axiom in international relations; many situations, like recognizing one ambassador over another or supporting one candidacy instead of another, require defined positions, which will be all the more controversial when it comes to non-democratic countries, as has started to occur.