Articles

International Relations and Human Rights Observatory

05-10-2021

05-10-2021Kyrgyzstan: how to break democracy in six months

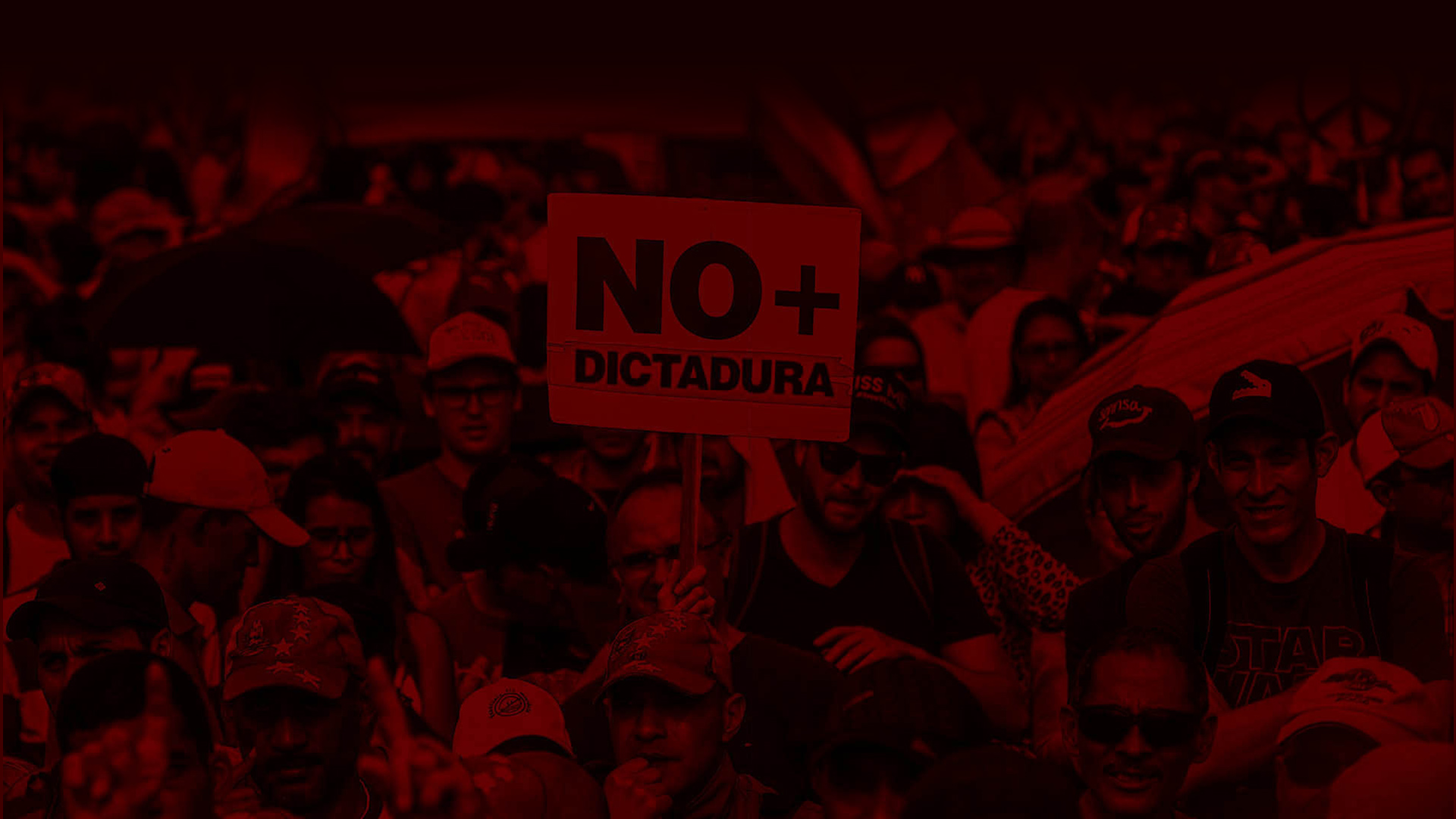

The once most democratic country in Central Asia it has been an almost direct flight from a chaotic and fragmented but democratic system to the heavy hand of a strong boss with increasing power and less opposition. Perhaps this distant country allows us to understand how weak democracy is when there are no solid institutions, how fragility entails instability and this opens the doors to charismatic leaders who proclaim themselves saviors just to take a step towards authoritarianism.

By Ignacio E. Hutin

Central Asia is much more than the Silk Road, a random spot on Marco Polo's maps, or that confusing set of "stan" suffixes. Of course, the geographical distance with Latin America does not help to strengthen ties and neither does the fact that Kazakhstan is the only Central Asian country with an embassy in the region. And yet it is convenient to look at Kyrgyzstan. The last year and the future that is already can be already foreseen for this country can be a good lesson about how quickly democratic institutions deteriorate, how a state can be broken in just 6 months.

Kyrgyzstan was the most democratic republic in its region, perhaps because it was the only one in which no local heir to the nomenklatura, the elite of the Soviet Communist Party, ruled. Even so, Askar Akayev was president since independence, in 1991, and until 2005, when he had to leave power (and the country) after a series of popular demonstrations originated in an alleged electoral fraud. He was succeeded by Kurmanbek Bakiyev, but five years later history repeated itself: demonstrations, resignation and escaping abroad. Two such similar events in just five years marked the need for a change. And Kyrgyzstan thus became the only country in the region with a parliamentary regime.

How did that experiment turn out? In a decade there were no less than 16 governments, including 5 headed by acting Prime Ministers. Kyrgyzstan never had a strong and one-man leadership as its neighbors in Turkmenistan or Uzbekistan did, but neither succeeded in consolidating a political culture that could lead to fair elections and recognized governments. It just fell in the middle. Parties and institutions are weak, especially in a parliamentary system, in which power is fragmented. But democratic aspirations remain despite difficulties. Or, rather, they remained.

In 2020 political fragmentation imploded. The fraud allegations that followed a very close parliamentary election led to demonstrations, as large as those in 2005 and 2010, but more violent. The seat of the government was burned down and politicians in prison were released, including Sadyr Japarov, a charismatic former Member of Parliament and Bakiyev's presidential adviser who had been convicted in 2017 of kidnapping a government official. The curious paths of a chaotic and heterogeneous revolution, coupled with successive resignations, led to Japarov becoming Prime Minister. He even became president for a month, meaning that he was Head of State and leader of the government at the same time. In just 10 days, he went from prison to having the sum of public power in his hands without even having received a single vote. The failed parliamentary elections were forgotten and not repeated.

Japarov emerged as a leader with a strong personality in the midst of chaos, as a savior, as a hero. Or as the strong hand that the country needed to finally achieve a stability that neither parliamentary nor presidential democracy had been able to provide. His popularity grew exponentially thanks to an anti-corruption and nationalist discourse, coupled with an atypical closeness to voters for the region. He spoke about nationalizing the gold mines, a mineral that represents more than 40% of the Central Asian country's exports, and about supporting migrant workers in countries like Russia and Turkey.

Japarov emerged as a leader with a strong personality in the midst of chaos, as a savior, as a hero. Or as the strong hand that the country needed to finally achieve a stability that neither parliamentary nor presidential democracy had been able to provide. His popularity grew exponentially thanks to an anti-corruption and nationalist discourse, coupled with an atypical closeness to voters for the region. He spoke about nationalizing the gold mines, a mineral that represents more than 40% of the Central Asian country's exports, and about supporting migrant workers in countries like Russia and Turkey.

In January he got almost 80% of the votes in an early presidential election in which less than 40% of the population participated, perhaps a reflection of mistrust in the system. At the same time, his proposal to return to a presidential regime was ratified. The new leader of Kyrgyzstan took office unopposed and with more power than any of his predecessors.

Japarov was already immersed in his triumphalism when, just 3 months later, on April 11th, a second constitutional referendum was held. This time the proposal was to increase the power of the president and reduce the number of members and responsibilities of Parliament. Other functions transferred from the legislative power to the executive included the possibility of calling referendums, removing privileges, and unilaterally appointing and removing members of the cabinet, judges, the attorney general, the president of the Central Bank and half of the members of the Central Electoral Committee, which would thus cease its independence. In addition, greater controls were proposed for non-governmental organizations, unions and political parties, and also the requirement of prior authorization to hold demonstrations, as is the case in Russia. On the other hand, it included the prohibition of activities and dissemination of information contrary to "the moral values and public conscience of the people." Without specifying what these values refer to, this article could lead to repression and abuse of power. In short, and according to the organization Human Rights Watch, the constitutional amendment project "undermines human rights norms and weakens checks and balances necessary to prevent abuses of power."

But warnings were not enough. The second referendum meant a new overwhelming victory for Japarov: the draft of the new Constitution was once again supported by almost 80% of the votes. Meanwhile, the failed parliamentary elections have yet to take place again. In other words, it was an interim parliament that initiated the process of constitutional amendments at the request of the president. Did it have the legitimacy to do so? It doesn't matter anymore.

In just six months, everything has been broken in Kyrgyzstan, the once most democratic country in Central Asia. It has been an almost direct flight from a chaotic and fragmented but democratic system to the heavy hand of a strong boss with increasing power and less opposition. Perhaps this distant country allows us to understand how weak democracy is when there are no solid institutions, how fragility entails instability and this opens the doors to charismatic leaders who proclaim themselves saviors just to take a step towards authoritarianism. Or perhaps it also serves to prove that Kafkaesque maxim: "every revolution evaporates and leaves behind only the slime of a new bureaucracy."

Ignacio E. HutinAdvisory CouncelorMaster in International Relations (University of Salvador, 2021), Graduate in Journalism (University of Salvador, 2014), specialized in Leadership in Humanitarian Emergencies (National Defense University, 2019) and studied photography (ARGRA, 2009). He is a focused in Eastern Europe, post-Soviet Eurasia and the Balkans. He received a scholarship from the Finnish State to carry out studies related to the Arctic at the University of Lapland (2012). He is the author of the books Saturn (2009), Deconstruction: Chronicles and Reflections from Post-Communist Eastern Europe (2018), Ukraine/Donbass: A Renewed Cold War (2021), and Ukraine: Chronicle from the Frontlines (2021).

Ignacio E. HutinAdvisory CouncelorMaster in International Relations (University of Salvador, 2021), Graduate in Journalism (University of Salvador, 2014), specialized in Leadership in Humanitarian Emergencies (National Defense University, 2019) and studied photography (ARGRA, 2009). He is a focused in Eastern Europe, post-Soviet Eurasia and the Balkans. He received a scholarship from the Finnish State to carry out studies related to the Arctic at the University of Lapland (2012). He is the author of the books Saturn (2009), Deconstruction: Chronicles and Reflections from Post-Communist Eastern Europe (2018), Ukraine/Donbass: A Renewed Cold War (2021), and Ukraine: Chronicle from the Frontlines (2021).

Central Asia is much more than the Silk Road, a random spot on Marco Polo's maps, or that confusing set of "stan" suffixes. Of course, the geographical distance with Latin America does not help to strengthen ties and neither does the fact that Kazakhstan is the only Central Asian country with an embassy in the region. And yet it is convenient to look at Kyrgyzstan. The last year and the future that is already can be already foreseen for this country can be a good lesson about how quickly democratic institutions deteriorate, how a state can be broken in just 6 months.

Kyrgyzstan was the most democratic republic in its region, perhaps because it was the only one in which no local heir to the nomenklatura, the elite of the Soviet Communist Party, ruled. Even so, Askar Akayev was president since independence, in 1991, and until 2005, when he had to leave power (and the country) after a series of popular demonstrations originated in an alleged electoral fraud. He was succeeded by Kurmanbek Bakiyev, but five years later history repeated itself: demonstrations, resignation and escaping abroad. Two such similar events in just five years marked the need for a change. And Kyrgyzstan thus became the only country in the region with a parliamentary regime.

How did that experiment turn out? In a decade there were no less than 16 governments, including 5 headed by acting Prime Ministers. Kyrgyzstan never had a strong and one-man leadership as its neighbors in Turkmenistan or Uzbekistan did, but neither succeeded in consolidating a political culture that could lead to fair elections and recognized governments. It just fell in the middle. Parties and institutions are weak, especially in a parliamentary system, in which power is fragmented. But democratic aspirations remain despite difficulties. Or, rather, they remained.

In 2020 political fragmentation imploded. The fraud allegations that followed a very close parliamentary election led to demonstrations, as large as those in 2005 and 2010, but more violent. The seat of the government was burned down and politicians in prison were released, including Sadyr Japarov, a charismatic former Member of Parliament and Bakiyev's presidential adviser who had been convicted in 2017 of kidnapping a government official. The curious paths of a chaotic and heterogeneous revolution, coupled with successive resignations, led to Japarov becoming Prime Minister. He even became president for a month, meaning that he was Head of State and leader of the government at the same time. In just 10 days, he went from prison to having the sum of public power in his hands without even having received a single vote. The failed parliamentary elections were forgotten and not repeated.

Japarov emerged as a leader with a strong personality in the midst of chaos, as a savior, as a hero. Or as the strong hand that the country needed to finally achieve a stability that neither parliamentary nor presidential democracy had been able to provide. His popularity grew exponentially thanks to an anti-corruption and nationalist discourse, coupled with an atypical closeness to voters for the region. He spoke about nationalizing the gold mines, a mineral that represents more than 40% of the Central Asian country's exports, and about supporting migrant workers in countries like Russia and Turkey.

Japarov emerged as a leader with a strong personality in the midst of chaos, as a savior, as a hero. Or as the strong hand that the country needed to finally achieve a stability that neither parliamentary nor presidential democracy had been able to provide. His popularity grew exponentially thanks to an anti-corruption and nationalist discourse, coupled with an atypical closeness to voters for the region. He spoke about nationalizing the gold mines, a mineral that represents more than 40% of the Central Asian country's exports, and about supporting migrant workers in countries like Russia and Turkey.

In January he got almost 80% of the votes in an early presidential election in which less than 40% of the population participated, perhaps a reflection of mistrust in the system. At the same time, his proposal to return to a presidential regime was ratified. The new leader of Kyrgyzstan took office unopposed and with more power than any of his predecessors.

Japarov was already immersed in his triumphalism when, just 3 months later, on April 11th, a second constitutional referendum was held. This time the proposal was to increase the power of the president and reduce the number of members and responsibilities of Parliament. Other functions transferred from the legislative power to the executive included the possibility of calling referendums, removing privileges, and unilaterally appointing and removing members of the cabinet, judges, the attorney general, the president of the Central Bank and half of the members of the Central Electoral Committee, which would thus cease its independence. In addition, greater controls were proposed for non-governmental organizations, unions and political parties, and also the requirement of prior authorization to hold demonstrations, as is the case in Russia. On the other hand, it included the prohibition of activities and dissemination of information contrary to "the moral values and public conscience of the people." Without specifying what these values refer to, this article could lead to repression and abuse of power. In short, and according to the organization Human Rights Watch, the constitutional amendment project "undermines human rights norms and weakens checks and balances necessary to prevent abuses of power."

But warnings were not enough. The second referendum meant a new overwhelming victory for Japarov: the draft of the new Constitution was once again supported by almost 80% of the votes. Meanwhile, the failed parliamentary elections have yet to take place again. In other words, it was an interim parliament that initiated the process of constitutional amendments at the request of the president. Did it have the legitimacy to do so? It doesn't matter anymore.

In just six months, everything has been broken in Kyrgyzstan, the once most democratic country in Central Asia. It has been an almost direct flight from a chaotic and fragmented but democratic system to the heavy hand of a strong boss with increasing power and less opposition. Perhaps this distant country allows us to understand how weak democracy is when there are no solid institutions, how fragility entails instability and this opens the doors to charismatic leaders who proclaim themselves saviors just to take a step towards authoritarianism. Or perhaps it also serves to prove that Kafkaesque maxim: "every revolution evaporates and leaves behind only the slime of a new bureaucracy."

Leer esta nota en Español

Leer esta nota en Español