Articles

International Relations and Human Rights Observatory

04-03-2024

04-03-2024The Big Business of Selling Gas to Europe: A Blank Check for Increasingly More Dictators

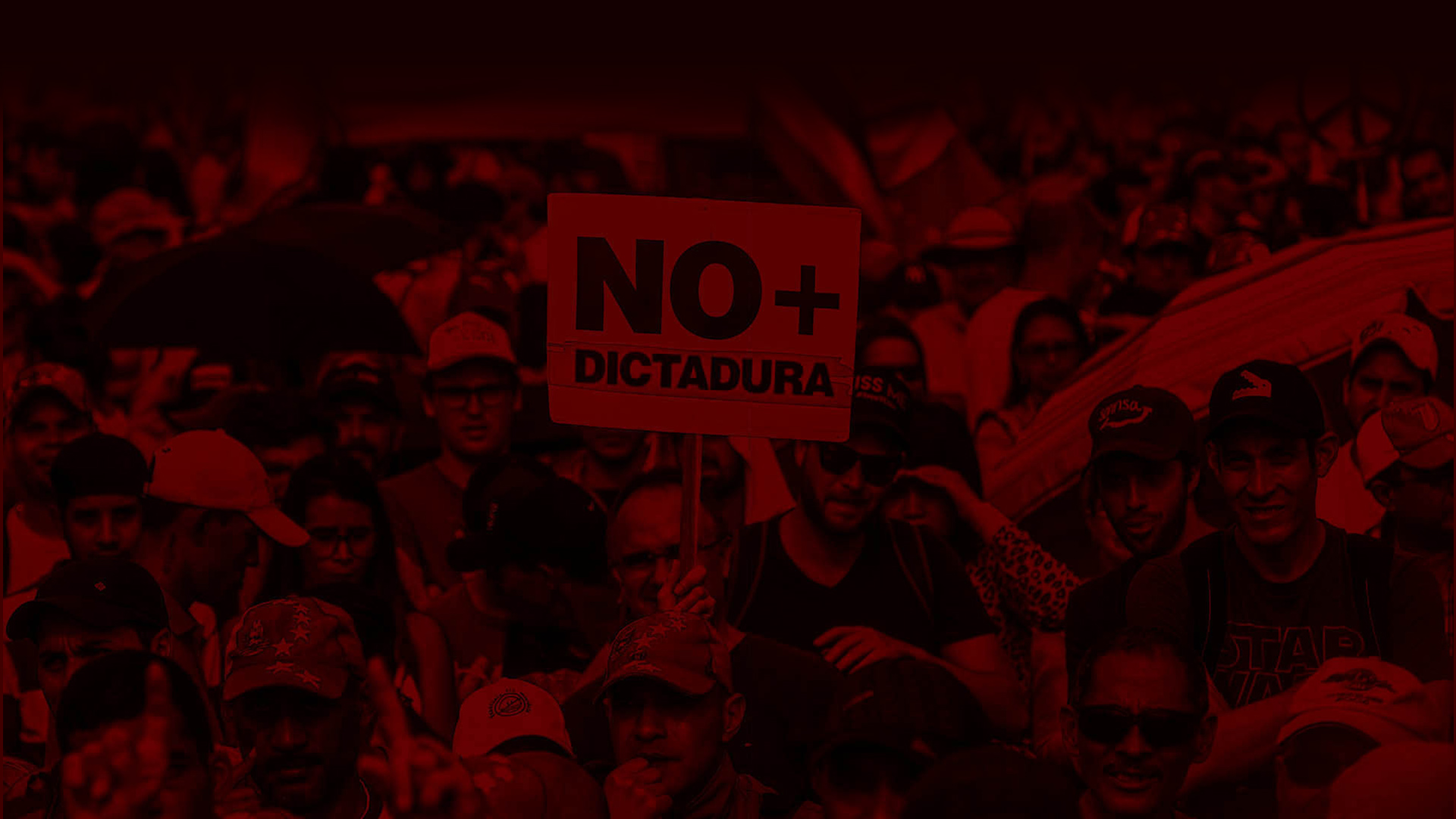

The European Union faces a great moral dilemma. But if it intends to exert some pressure on Russia and punish its leaders for violations of international law, it is of little use if it ends up endorsing other states that commit equally serious crimes in such a sustained manner.

By Ignacio E. Hutin

The Minister of Foreign Affairs of Turkmenistan, Rashid Meredov, met in Brussels with Josep Borrell, the man in charge of the European Union’s foreign affairs, and other officials. Photos were taken, there were smiles, dialogue, and the signing of the Protocol of Collaboration and Cooperation Agreement. The Turkmen also held meetings with businessmen, with whom he discussed the commercial potential and the interest of his country in supplying gas to Europe. Just a week before, he had been in Vienna, in a similar meeting to discuss energy cooperation. It is not by coincidence, but part of a process.

Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow, former president of Turkmenistan and father of the current president, Serdar Berdimuhamedow, maintains certain political administrative control, particularly regarding the production and marketing of gas. Hydrocarbons, and especially gas, represent about 90% of Turkmenistan’s exports. At the beginning of March, the former leader traveled to Turkey and met with President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to discuss the provision to that country, but also beyond, towards Europe. An agreement was signed that will initiate commercial exchange. And both men ended up very satisfied.

But does the European Union really want to buy gas from one of the 10 most repressive and authoritarian countries on the planet, not much different from North Korea or Afghanistan under Taliban control?

Turkmenistan’s human rights record is dismal: there is no freedom of the press, religion, association, expression, information, or movement. According to the latest Human Rights Watch report, many people "unjustly imprisoned remain behind bars," "the fate of dozens of victims of enforced disappearances is still unknown," and "torture and ill-treatment in custody persist". There are no changes in the matter, nor have there been since it declared independence from the Soviet Union in 1991.

The Central Asian country has had only three presidents: Saparmurat Niyazov died in power in 2006 and only ran in two elections, without rivals, in 26 years; Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow was succeeded by his son in 2022. In all four elections since Niyazov’s death, there wasn’t even an attempt to show some democratic aspiration. In fact, in two of them, 2007 and 2012, there were only candidates from the official party.

But something did change in this mostly desert republic. In 2017, the Russian company Gazprom announced that it would no longer buy Turkmen gas and would replace it with Uzbek production. That same year, Turkmenistan stopped selling to Iran due to an alleged debt. It then became solely dependent on China. Although in recent years, Russia went from buying zero gas to 10 billion cubic meters (bcm) annually, it still represents about 25% of what it bought in the mid-2000s, and Beijing constitutes the only relevant customer of a country that has the fourth largest gas reserves in the world.

This has led to an extensive economic crisis that the Turkmen government simply hides and, therefore, does not take measures to address the ongoing food insecurity. Official data is so unreliable or downright non-existent that the World Bank does not publish information about Turkmenistan. In addition to this, commercial relations with Russia in energy matters are not the best: Moscow buys little but seeks to politically pressure to sell gas to China using pipelines in Turkmenistan, while reducing prices to Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan so that the Berdimuhamedow fiefdom cannot compete.

But the all-powerful father and son had a stroke of luck: Russia’s invasion to Ukraine in 2022 resulted in the imposition of commercial sanctions and the European Union buying nearly 70% less from Moscow than in 2021. Europe needs alternatives, and Turkmenistan appears as an option, although geographic distance poses an obstacle.

For this, the former Soviet republic has two allies. On the one hand, Erdogan’s Turkey, whose democratic standards and respect for human rights have plummeted in the last decade as the current president and former prime minister accumulates more and more power. The idea is for Turkey to become a regional energy hub for gas exports, importing via pipelines from Russia, Azerbaijan, and Iran, and redistributing to Europe, in addition to ensuring internal supply. If Turkmenistan wants to enter this game, it has two possibilities: either send via Iran, an option that is not favored by the EU, or build a pipeline across the Caspian Sea to connect with Azerbaijan, which Russia and Iran oppose. Here comes the second potential ally.

Azerbaijan’s democracy indices are worse than Turkey’s: repression to dissidents, attacks and detentions of critics, torture, and restrictions on press freedom. Additionally, according to the latest annual report from Freedom House, "corruption is pervasive. In the absence of a free press and an independent judiciary, officials are held accountable for their corrupt behavior only when it satisfies the needs of a more powerful or better-connected figure."

This country has had only two presidents since its independence in 1991: Heydar and Ilham Aliyev. Father and son. The first one died in power in 2003; the second one changed the Constitution to increase the presidential term to 7 years and allow for unlimited reelections. To understand the general situation of the country, it is enough to say that in the last elections, in February, Aliyev officially obtained over 92%. Observers from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) announced that there was no real competition and there were "serious electoral flaws and restrictions imposed on the media."

Despite this, among others, Charles Michel, President of the European Council, congratulated the Azerbaijani for his highly expected victory and also took the opportunity to discuss cooperation between Azerbaijan and the continental bloc in energy matters.

In 2022, with the aim of breaking its dependence on Russian gas, the EU signed an agreement with Azerbaijan that involves doubling Azerbaijani gas imports by 2027 to 20 bcm annually. However, Brussels failed to establish conditions for future cooperation that would help ensure improvements in human rights. And the government in Baku has refused to allow the organization to provide grants to local civil society groups. Still, Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, described Azerbaijan as "a reliable partner."

Almost exactly a year after the signing, Azerbaijan attacked the civilian population of Nagorno-Karabakh, a region in the east of the country inhabited almost entirely by Armenians and outside the de facto control of the central government since the dissolution of the Soviet Union. In just one day, and citing the need to take anti-terrorism actions, Aliyev’s forces caused the death of 27 Armenians. Over a hundred thousand people, almost the entire ethnically Armenian population of the area, fled the country.

It was the culmination of a process initiated in late 2022, during which Azerbaijan blocked access to Nagorno-Karabakh, including the entry of humanitarian aid and the transport of patients from the International Committee of the Red Cross, as well as cutting off gas and electricity services. The International Court of Justice twice ordered Baku to end the blockade, but Aliyev ignored the demand. Russia, increasingly distant from Armenia, tacitly supported it. And last February’s elections were snap so that for the first time, voting could take place in the reclaimed Nagorno-Karabakh, an area already practically uninhabited.

So, Brussels imposes sanctions and distances itself from a Russian government that attacks civilian population, represses dissidents, and proclaims that, as happened in mid-March, its president is re-elected with 88% of the votes. But it also signs agreements and negotiates with an Azerbaijani government that attacks civilian population, represses dissidents, and proclaims that, as happened in February, its president is re-elected with 92% of the votes.

And then it goes beyond that and signs agreements with a Turkmen government whose levels of repression are not far from those of North Korea.

Azerbaijan has become one of the main gas suppliers to the European Union. At the same time, Russia continues to sell to the West, directly and also through Turkey, even to those countries that do not openly buy Russian products. Something similar, albeit on a smaller scale, happens with Iran. And Turkmenistan appears on the horizon as a next major supplier. The Berdimuhamedows could become the new members of the until now Moscow-Ankara-Baku triad, which exerts political and commercial influence thanks to a European hydrocarbon dependency that has not diminished despite the announcements that followed the Russian invasion to Ukraine.

The European Union faces a great moral dilemma. But if it intends to exert some pressure on Russia and punish its leaders for violations of international law, it is of little use if it ends up endorsing other states that commit equally serious crimes in such a sustained manner. More and more autocratic leaders understand that their hydrocarbons mean a blank check to do whatever they want. With this implicit endorsement from the European Union, a scenario like that of Ukraine could repeat itself in the near future in other countries.

Ignacio E. HutinAdvisory CouncelorMaster in International Relations (University of Salvador, 2021), Graduate in Journalism (University of Salvador, 2014), specialized in Leadership in Humanitarian Emergencies (National Defense University, 2019) and studied photography (ARGRA, 2009). He is a focused in Eastern Europe, post-Soviet Eurasia and the Balkans. He received a scholarship from the Finnish State to carry out studies related to the Arctic at the University of Lapland (2012). He is the author of the books Saturn (2009), Deconstruction: Chronicles and Reflections from Post-Communist Eastern Europe (2018), Ukraine/Donbass: A Renewed Cold War (2021), and Ukraine: Chronicle from the Frontlines (2021).

Ignacio E. HutinAdvisory CouncelorMaster in International Relations (University of Salvador, 2021), Graduate in Journalism (University of Salvador, 2014), specialized in Leadership in Humanitarian Emergencies (National Defense University, 2019) and studied photography (ARGRA, 2009). He is a focused in Eastern Europe, post-Soviet Eurasia and the Balkans. He received a scholarship from the Finnish State to carry out studies related to the Arctic at the University of Lapland (2012). He is the author of the books Saturn (2009), Deconstruction: Chronicles and Reflections from Post-Communist Eastern Europe (2018), Ukraine/Donbass: A Renewed Cold War (2021), and Ukraine: Chronicle from the Frontlines (2021).

The Minister of Foreign Affairs of Turkmenistan, Rashid Meredov, met in Brussels with Josep Borrell, the man in charge of the European Union’s foreign affairs, and other officials. Photos were taken, there were smiles, dialogue, and the signing of the Protocol of Collaboration and Cooperation Agreement. The Turkmen also held meetings with businessmen, with whom he discussed the commercial potential and the interest of his country in supplying gas to Europe. Just a week before, he had been in Vienna, in a similar meeting to discuss energy cooperation. It is not by coincidence, but part of a process.

Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow, former president of Turkmenistan and father of the current president, Serdar Berdimuhamedow, maintains certain political administrative control, particularly regarding the production and marketing of gas. Hydrocarbons, and especially gas, represent about 90% of Turkmenistan’s exports. At the beginning of March, the former leader traveled to Turkey and met with President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to discuss the provision to that country, but also beyond, towards Europe. An agreement was signed that will initiate commercial exchange. And both men ended up very satisfied.

But does the European Union really want to buy gas from one of the 10 most repressive and authoritarian countries on the planet, not much different from North Korea or Afghanistan under Taliban control?

Turkmenistan’s human rights record is dismal: there is no freedom of the press, religion, association, expression, information, or movement. According to the latest Human Rights Watch report, many people "unjustly imprisoned remain behind bars," "the fate of dozens of victims of enforced disappearances is still unknown," and "torture and ill-treatment in custody persist". There are no changes in the matter, nor have there been since it declared independence from the Soviet Union in 1991.

The Central Asian country has had only three presidents: Saparmurat Niyazov died in power in 2006 and only ran in two elections, without rivals, in 26 years; Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow was succeeded by his son in 2022. In all four elections since Niyazov’s death, there wasn’t even an attempt to show some democratic aspiration. In fact, in two of them, 2007 and 2012, there were only candidates from the official party.

But something did change in this mostly desert republic. In 2017, the Russian company Gazprom announced that it would no longer buy Turkmen gas and would replace it with Uzbek production. That same year, Turkmenistan stopped selling to Iran due to an alleged debt. It then became solely dependent on China. Although in recent years, Russia went from buying zero gas to 10 billion cubic meters (bcm) annually, it still represents about 25% of what it bought in the mid-2000s, and Beijing constitutes the only relevant customer of a country that has the fourth largest gas reserves in the world.

This has led to an extensive economic crisis that the Turkmen government simply hides and, therefore, does not take measures to address the ongoing food insecurity. Official data is so unreliable or downright non-existent that the World Bank does not publish information about Turkmenistan. In addition to this, commercial relations with Russia in energy matters are not the best: Moscow buys little but seeks to politically pressure to sell gas to China using pipelines in Turkmenistan, while reducing prices to Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan so that the Berdimuhamedow fiefdom cannot compete.

But the all-powerful father and son had a stroke of luck: Russia’s invasion to Ukraine in 2022 resulted in the imposition of commercial sanctions and the European Union buying nearly 70% less from Moscow than in 2021. Europe needs alternatives, and Turkmenistan appears as an option, although geographic distance poses an obstacle.

For this, the former Soviet republic has two allies. On the one hand, Erdogan’s Turkey, whose democratic standards and respect for human rights have plummeted in the last decade as the current president and former prime minister accumulates more and more power. The idea is for Turkey to become a regional energy hub for gas exports, importing via pipelines from Russia, Azerbaijan, and Iran, and redistributing to Europe, in addition to ensuring internal supply. If Turkmenistan wants to enter this game, it has two possibilities: either send via Iran, an option that is not favored by the EU, or build a pipeline across the Caspian Sea to connect with Azerbaijan, which Russia and Iran oppose. Here comes the second potential ally.

Azerbaijan’s democracy indices are worse than Turkey’s: repression to dissidents, attacks and detentions of critics, torture, and restrictions on press freedom. Additionally, according to the latest annual report from Freedom House, "corruption is pervasive. In the absence of a free press and an independent judiciary, officials are held accountable for their corrupt behavior only when it satisfies the needs of a more powerful or better-connected figure."

This country has had only two presidents since its independence in 1991: Heydar and Ilham Aliyev. Father and son. The first one died in power in 2003; the second one changed the Constitution to increase the presidential term to 7 years and allow for unlimited reelections. To understand the general situation of the country, it is enough to say that in the last elections, in February, Aliyev officially obtained over 92%. Observers from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) announced that there was no real competition and there were "serious electoral flaws and restrictions imposed on the media."

Despite this, among others, Charles Michel, President of the European Council, congratulated the Azerbaijani for his highly expected victory and also took the opportunity to discuss cooperation between Azerbaijan and the continental bloc in energy matters.

In 2022, with the aim of breaking its dependence on Russian gas, the EU signed an agreement with Azerbaijan that involves doubling Azerbaijani gas imports by 2027 to 20 bcm annually. However, Brussels failed to establish conditions for future cooperation that would help ensure improvements in human rights. And the government in Baku has refused to allow the organization to provide grants to local civil society groups. Still, Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, described Azerbaijan as "a reliable partner."

Almost exactly a year after the signing, Azerbaijan attacked the civilian population of Nagorno-Karabakh, a region in the east of the country inhabited almost entirely by Armenians and outside the de facto control of the central government since the dissolution of the Soviet Union. In just one day, and citing the need to take anti-terrorism actions, Aliyev’s forces caused the death of 27 Armenians. Over a hundred thousand people, almost the entire ethnically Armenian population of the area, fled the country.

It was the culmination of a process initiated in late 2022, during which Azerbaijan blocked access to Nagorno-Karabakh, including the entry of humanitarian aid and the transport of patients from the International Committee of the Red Cross, as well as cutting off gas and electricity services. The International Court of Justice twice ordered Baku to end the blockade, but Aliyev ignored the demand. Russia, increasingly distant from Armenia, tacitly supported it. And last February’s elections were snap so that for the first time, voting could take place in the reclaimed Nagorno-Karabakh, an area already practically uninhabited.

So, Brussels imposes sanctions and distances itself from a Russian government that attacks civilian population, represses dissidents, and proclaims that, as happened in mid-March, its president is re-elected with 88% of the votes. But it also signs agreements and negotiates with an Azerbaijani government that attacks civilian population, represses dissidents, and proclaims that, as happened in February, its president is re-elected with 92% of the votes.

And then it goes beyond that and signs agreements with a Turkmen government whose levels of repression are not far from those of North Korea.

Azerbaijan has become one of the main gas suppliers to the European Union. At the same time, Russia continues to sell to the West, directly and also through Turkey, even to those countries that do not openly buy Russian products. Something similar, albeit on a smaller scale, happens with Iran. And Turkmenistan appears on the horizon as a next major supplier. The Berdimuhamedows could become the new members of the until now Moscow-Ankara-Baku triad, which exerts political and commercial influence thanks to a European hydrocarbon dependency that has not diminished despite the announcements that followed the Russian invasion to Ukraine.

The European Union faces a great moral dilemma. But if it intends to exert some pressure on Russia and punish its leaders for violations of international law, it is of little use if it ends up endorsing other states that commit equally serious crimes in such a sustained manner. More and more autocratic leaders understand that their hydrocarbons mean a blank check to do whatever they want. With this implicit endorsement from the European Union, a scenario like that of Ukraine could repeat itself in the near future in other countries.

Leer esta nota en Español

Leer esta nota en Español