Diálogo Latino Cubano

Promoción de la Apertura Política en Cuba

29-06-2020

29-06-2020A disgrace to the region: Latin America's «leader» on the UN Human Rights Council is a dictatorship

Cuba will most likely be elected to its fifth term in the HRC, which will enable it to run for re-election in 2023. By returning to the Council in 2023, Cuba would then complete 18 of the 20 years of the HRC’s existence in one of its seats. Other countries with a similar record, such as Saudi Arabia or China, could achieve the same. The fact that Cuba manages to maintain its «leadership», spending as many years as possible in an organization that it makes fun of, says a lot about the lack of real leadership in Latin America regarding the defense of human rights.Por Gabriel C. Salvia

Since 2006, when the Human Rights Council (HRC) was created within the UN system to replace the former Commission, it is the dictatorships that have been on the Council longest, one of them belonging to the region of Latin America and Caribbean: Cuba.

The HRC is composed of 47 UN member states, which are elected universally through direct and secret ballot by the majority of members of the General Assembly, and are grouped as follows: African States: 13; Asian States: 13; Eastern European States: 6; Latin American and Caribbean States: 8; Western European and other States: 7. Members of the Council serve for a period of three years and are not eligible for immediate re-election after serving two consecutive terms. Accordingly, Cuba served four terms in the HRC: 2007 to 2009; 2010 to 2012; 2014 to 2016; 2017 to 2019; and has already announced its candidacy for the period of 2021 to 2023.

The Resolution which created the HRC states that participation in the Council shall be open to all UN member states and that, while electing the members of the Council, they should take into account the candidates' contribution to the promotion and protection of human rights as well as their voluntary pledges and commitments thereto. Furthermore, the members elected to the Council should uphold the highest standards in the promotion and protection of human rights, fully cooperate with the Council and be reviewed by means of the Universal Periodic Review mechanism during their term of membership. On the latter, a detailed report published by CADAL and written by Brian Schapira and Roxana Perel documents Cuba's lack of commitment to the universal human rights system (“La falta de compromiso de Cuba con el sistema universal de derechos humanos”).

In addition to the above, it should be noted that Cuba is the only country in Latin America that has not yet ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Since signing both covenants in 2008, the Cuban government has only ever responded that it was “examining them”, when it faced recommendations for their ratification made by several countries during Cuba’s second and third Universal Periodic Reviews at the HRC, by the treaty-based bodies Cuba is part of, by various Special Procedures of the Council, and by the High Commissioner for Human Rights herself, Michelle Bachelet. It is odd that they have been looking into the ratification of both covenants for twelve years, but that from one year to the next they have been able to draft and adopt a new Constitution, a document that supposedly too requires prior “examination”.

The truth is that Cuba does not ratify either of these two covenants because, by doing so, it would be assuming the legal obligation to implement their provisions and to report periodically to a United Nations "treaty-based body" composed of independent experts. Ten such bodies monitor the implementation of those Treaties and Optional Protocols through two main channels. Firstly, through periodic reports on the situation of particular rights in a State that is party to the respective Treaty and, secondly, through communications submitted by individuals. The treaty-based bodies may also undertake country visits and research.

Despite this record, Cuba will most likely be elected to its fifth term in the HRC, which will enable it to run for re-election in 2023. By returning to the Council in 2023, Cuba would then complete 18 of the 20 years of the HRC’s existence in one of its seats. Other countries with a similar record, such as Saudi Arabia or China, could achieve the same.

As a reminder, on 28 October 2016, when one third of the Council was renewed, China obtained no less than 180 votes, leaving no doubt that it had the support of several developed democracies. Cuba also obtained 160 votes.

In the light of the upcoming election to renew the HRC in October, Chile and Peru are hesitating to run for re-election, which would pave the way for the Cuban dictatorship even further. Another country that could run for re-election is Mexico, which is already serving its 12th year on the council as well. Unlike Colombia, which never joined the HRC, Mexico is not ashamed to join, even though it is the region's flawed democracy with the most serious cases of human rights violations.

Last year, the Venezuelan dictatorship ran for a seat and managed to enter the HRC, obtaining more votes than Costa Rica, one of the countries of the region that is known to have outstanding democratic institutions. Brazil also has been re-elected to the HRC in 2019, having a government whose president defends the human rights violations committed during the last military dictatorship.

Therefore, the fact that Cuba manages to maintain its "leadership", spending as many years as possible in an organization that it makes fun of, says a lot about the lack of real leadership in Latin America regarding the defense of human rights.

Given this situation, it only remains to embarrass the Cuban dictatorship, pointing out that it has no commitment to the universal system of human rights; that it is exceptional in Latin America for not having ratified two of the core human rights treaties; and that it is the most undemocratic country in the region for being led by a single-party regime that criminalizes the rights to freedom of association, assembly, press, expression and political participation. In this sense, high authorities of democratic countries, legislators, former presidents and chancellors, political and social leaders, journalists and intellectuals of Latin America should publicly reject Cuba's renewed candidacy to the HRC, making those who violate human rights feel more ashamed than those who defend them.

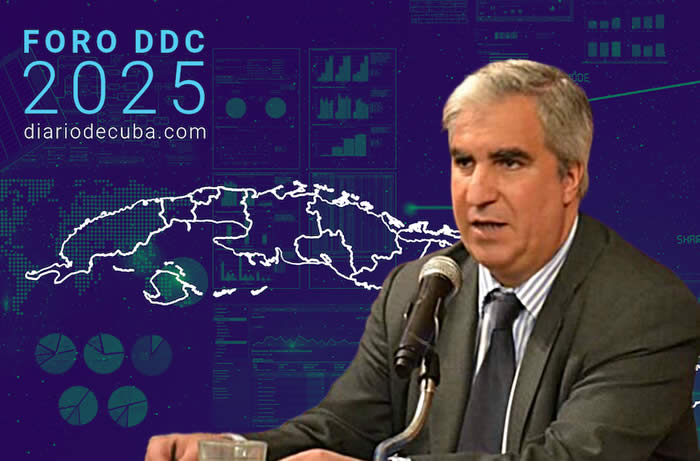

Gabriel C. Salvia is General Director of CADAL, a private foundation whose mission is to promote human rights and international democratic solidarity.

Gabriel C. SalviaDirector GeneralActivista de derechos humanos enfocado en la solidaridad democrática internacional. En 2024 recibió el Premio Gratias Agit del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de la República Checa. Es autor de los libros "Memoria, derechos humanos y solidaridad democrática internacional" (2024) y "Bailando por un espejismo: apuntes sobre política, economía y diplomacia en los gobiernos de Cristina Fernández de Kirchner" (2017). Además, compiló varios libros, entre ellos "75 años de la Declaración Universal de Derechos Humanos: Miradas desde Cuba" (2023), "Los derechos humanos en las relaciones internacionales y la política exterior" (2021), "Desafíos para el fortalecimiento democrático en la Argentina" (2015), "Un balance político a 30 años del retorno a la democracia en Argentina" (2013) y "Diplomacia y Derechos Humanos en Cuba" (2011), Sus columnas de opinión han sido publicadas en varios medios en español. Actualmente publica en Clarín, Perfil, Infobae y La Nación, de Argentina. Ha participado en eventos internacionales en América Latina, África, Asia, Europa, los Balcanes y en Estados Unidos. Desde 1992 se desempeña como director en Organizaciones de la Sociedad Civil y es miembro fundador de CADAL. Como periodista, trabajó entre 1992 y 1997 en gráfica, radio y TV especializado en temas parlamentarios, políticos y económicos, y posteriormente contribuyó con entrevistas en La Nación y Perfil.

Gabriel C. SalviaDirector GeneralActivista de derechos humanos enfocado en la solidaridad democrática internacional. En 2024 recibió el Premio Gratias Agit del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de la República Checa. Es autor de los libros "Memoria, derechos humanos y solidaridad democrática internacional" (2024) y "Bailando por un espejismo: apuntes sobre política, economía y diplomacia en los gobiernos de Cristina Fernández de Kirchner" (2017). Además, compiló varios libros, entre ellos "75 años de la Declaración Universal de Derechos Humanos: Miradas desde Cuba" (2023), "Los derechos humanos en las relaciones internacionales y la política exterior" (2021), "Desafíos para el fortalecimiento democrático en la Argentina" (2015), "Un balance político a 30 años del retorno a la democracia en Argentina" (2013) y "Diplomacia y Derechos Humanos en Cuba" (2011), Sus columnas de opinión han sido publicadas en varios medios en español. Actualmente publica en Clarín, Perfil, Infobae y La Nación, de Argentina. Ha participado en eventos internacionales en América Latina, África, Asia, Europa, los Balcanes y en Estados Unidos. Desde 1992 se desempeña como director en Organizaciones de la Sociedad Civil y es miembro fundador de CADAL. Como periodista, trabajó entre 1992 y 1997 en gráfica, radio y TV especializado en temas parlamentarios, políticos y económicos, y posteriormente contribuyó con entrevistas en La Nación y Perfil.

Since 2006, when the Human Rights Council (HRC) was created within the UN system to replace the former Commission, it is the dictatorships that have been on the Council longest, one of them belonging to the region of Latin America and Caribbean: Cuba.

The HRC is composed of 47 UN member states, which are elected universally through direct and secret ballot by the majority of members of the General Assembly, and are grouped as follows: African States: 13; Asian States: 13; Eastern European States: 6; Latin American and Caribbean States: 8; Western European and other States: 7. Members of the Council serve for a period of three years and are not eligible for immediate re-election after serving two consecutive terms. Accordingly, Cuba served four terms in the HRC: 2007 to 2009; 2010 to 2012; 2014 to 2016; 2017 to 2019; and has already announced its candidacy for the period of 2021 to 2023.

The Resolution which created the HRC states that participation in the Council shall be open to all UN member states and that, while electing the members of the Council, they should take into account the candidates' contribution to the promotion and protection of human rights as well as their voluntary pledges and commitments thereto. Furthermore, the members elected to the Council should uphold the highest standards in the promotion and protection of human rights, fully cooperate with the Council and be reviewed by means of the Universal Periodic Review mechanism during their term of membership. On the latter, a detailed report published by CADAL and written by Brian Schapira and Roxana Perel documents Cuba's lack of commitment to the universal human rights system (“La falta de compromiso de Cuba con el sistema universal de derechos humanos”).

In addition to the above, it should be noted that Cuba is the only country in Latin America that has not yet ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Since signing both covenants in 2008, the Cuban government has only ever responded that it was “examining them”, when it faced recommendations for their ratification made by several countries during Cuba’s second and third Universal Periodic Reviews at the HRC, by the treaty-based bodies Cuba is part of, by various Special Procedures of the Council, and by the High Commissioner for Human Rights herself, Michelle Bachelet. It is odd that they have been looking into the ratification of both covenants for twelve years, but that from one year to the next they have been able to draft and adopt a new Constitution, a document that supposedly too requires prior “examination”.

The truth is that Cuba does not ratify either of these two covenants because, by doing so, it would be assuming the legal obligation to implement their provisions and to report periodically to a United Nations "treaty-based body" composed of independent experts. Ten such bodies monitor the implementation of those Treaties and Optional Protocols through two main channels. Firstly, through periodic reports on the situation of particular rights in a State that is party to the respective Treaty and, secondly, through communications submitted by individuals. The treaty-based bodies may also undertake country visits and research.

Despite this record, Cuba will most likely be elected to its fifth term in the HRC, which will enable it to run for re-election in 2023. By returning to the Council in 2023, Cuba would then complete 18 of the 20 years of the HRC’s existence in one of its seats. Other countries with a similar record, such as Saudi Arabia or China, could achieve the same.

As a reminder, on 28 October 2016, when one third of the Council was renewed, China obtained no less than 180 votes, leaving no doubt that it had the support of several developed democracies. Cuba also obtained 160 votes.

In the light of the upcoming election to renew the HRC in October, Chile and Peru are hesitating to run for re-election, which would pave the way for the Cuban dictatorship even further. Another country that could run for re-election is Mexico, which is already serving its 12th year on the council as well. Unlike Colombia, which never joined the HRC, Mexico is not ashamed to join, even though it is the region's flawed democracy with the most serious cases of human rights violations.

Last year, the Venezuelan dictatorship ran for a seat and managed to enter the HRC, obtaining more votes than Costa Rica, one of the countries of the region that is known to have outstanding democratic institutions. Brazil also has been re-elected to the HRC in 2019, having a government whose president defends the human rights violations committed during the last military dictatorship.

Therefore, the fact that Cuba manages to maintain its "leadership", spending as many years as possible in an organization that it makes fun of, says a lot about the lack of real leadership in Latin America regarding the defense of human rights.

Given this situation, it only remains to embarrass the Cuban dictatorship, pointing out that it has no commitment to the universal system of human rights; that it is exceptional in Latin America for not having ratified two of the core human rights treaties; and that it is the most undemocratic country in the region for being led by a single-party regime that criminalizes the rights to freedom of association, assembly, press, expression and political participation. In this sense, high authorities of democratic countries, legislators, former presidents and chancellors, political and social leaders, journalists and intellectuals of Latin America should publicly reject Cuba's renewed candidacy to the HRC, making those who violate human rights feel more ashamed than those who defend them.

Gabriel C. Salvia is General Director of CADAL, a private foundation whose mission is to promote human rights and international democratic solidarity.

Read it in English

Read it in English